In Print

|

|

|

Entertainment

Design

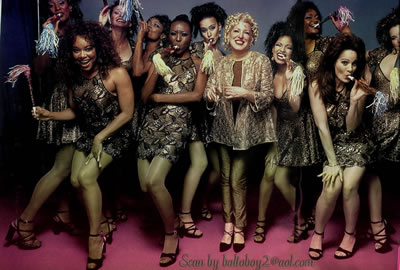

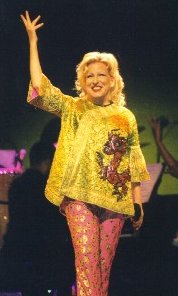

With the incredibly successful Divine Miss Millennium tour, Bette Midler has cemented her reputation as the hardest working woman in show business. A claimed diva long before a certain cable music channel began somewhat indiscriminately conferring the title on others, the Divine Miss M--Harlettes in tow--performs a two-and-a-half-hour show each night with one intermission. While weaving in a few songs from her latest CD, Bathhouse Betty, Midler took great care to revisit her Hawaiian roots, as well as old favorites like mermaid Delores De Lago and the wheelchair-enabled De Lago sisters. From her opening stance on the top of the world, to the flashy "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" encore, it's a far cry from your average pop singer's tour. Midler frequently addresses the audience with such winking bon mots as, "I know you love me and I accept your love with such graciousness, don't I?" She also completely scripts her show with help from writers Bruce Vilanch, Jonathan Tolins, and Mark Waldrop (who is also the tour's production supervisor). Vilanch visited the tour on a regular basis to add city-specific jokes to the show. For instance, at the Nassau Coliseum show on Long Island, NY, Midler quipped about the show's late start: "We would have started the show earlier, but we took the LIRR to get here and we had to change in Jamaica--you know how it is." That attention to detail set this tour apart. "You just don't see that many arena tours that are as traditional in their presentation," says lighting designer Allen Branton. "The content is so strong, as is her performance, the writing, the choreography, and the wardrobe--it's all there in that Broadway style. That's really hard to do on the road every day. She made quite a profound financial commitment and a huge time commitment to it. She's one of the hardest working people I've ever seen." Midler and her longtime collaborator, production/costume designer Robert deMora, began discussing ideas for the tour as early as February 1999. "We tried to figure out what the ultimate point of this millennium would be, because the tour's main date was obviously the New Year's show in Las Vegas," deMora explains. "We threw around the same ideas most people probably do--what the past has taught us and what the future might hold--and we went from there." Midler

and deMora visited the picture collection at the New York Public Library to loo In the interest of seeing all the staging possibilities, deMora brought Midler with him to visit Tait Towers, where owner Michael Tait and general manager James "Winky" Fairorth gave them a full tour. "We had a meeting there in the spring because I wanted to show her what we could do," deMora says. "Usually we have a stage that doesn't do anything, and I just do some tricks scenically. I wanted to show her the elevators and treadmills and all of those devices I thought we could use this time, in lieu of a lot of scenery." Most of the show's props and scenic elements come up from the stage floor via elevator. "Bette likes people to make entrances from the wings as you do in traditional theatre, but we're playing in such an open space that we didn't have our wings," deMora says. "This way we could bring them out of the floor, so they come in vertically rather than horizontally, and then leave by descending." The show opens with Midler on top of the world--literally. She appears atop a huge globe, which soon breaks apart; she is then delivered to the stage floor. "The elevator that gets her to the top of the world and down is called a Ribbonlift," explains Tait. "Stardrive invented it. It's like having three stainless-steel, giant tape measures that zipper together as they go up. Imagine three tape measures at 120 [degrees] angles to each other unrolling and zipping together to make a triangular tower and then disappearing into nothing. It's fabulous. And to Bob's credit, he used it again at the end of the first act to create the volcano." "One of the biggest challenges to do from a production standpoint was to incorporate all of the theatrical ideas into a proscenium show where you could sell 270 [degrees]," Fairorth says. "They do it, but it isn't easy keeping those sightlines upstage of the downstage edge of the set. Bette wanted everything--and she's got pretty much everything. Bob gave us his vision and the freedom to mold it into something that was real, which we did with the help of Bugzee [production manager John Hougdahl]. He really helped from a production standpoint by merging everyone together." One of deMora's strongest requirements was that the stage deck be as low as possible. "It's only 5' off the floor of the arena and that's a very low height for people to be making entrances from below and changing costumes beneath," he acknowledges. "I have about six rolling desk chairs and we just roll around under there like little gremlins. We've not had one accident; no one has hit his head. But it was a big bone of contention, because most everybody thought that it needed to be at least 6' high, if not more. But then the people on the arena floor would be at Bette's knees. I did succeed in getting the monitor shelf down lower than the stage level, which was a big accomplishment at 4' high. Then the thrust that goes out into the audience gives Bette the ability to have those intimate moments by breaking the proscenium." One Ribbonlift, three elevators, a treadmill, two trap doors, and a multitude of costumes and props fit into a tidy eight trucks. "Ricky Martin's tour takes about 22 trucks, so we're actually a small-size show," deMora says. "We don't want to be overproduced; we felt we should stay with our roots. As Bette says in the show, `We've gone high tech, but we're still lowbrow.' We haven't really even gone high tech by today's standards--just more so than we usually do." Production supervisor Waldrop functions as the show's director. "We had to figure out ways to use all of these devices Bob found," he says. "Ultimately we came up with a package where we used everything more than once and usually in a different way--never the same way twice. The stage is just packed with surprises."

The creative team of Midler, deMora, Waldrop, Branton, and choreographer Toni Basil had regular meetings to flesh out those surprises. "When we finally decided we would try to do the stage at one end of the arena so it has a proscenium feel, we added circular curtain tracks for the scrims," deMora explains. "So I played with putting Bette's face on the moon, which is on the front scrim. When the band is upstage, Bette likes the proscenium and drapes and curtains behind her, so the stage is not open constantly. We also had to deal with the fact that the band has to see her and the dancers. So whenever we pull a scrim so she has a backdrop to perform against, it must be see-through so the band can see what's going on. "For the opening section where the, globe breaks apart, I thought it should be the cosmos and she should rise to the top and appear on top of the world," deMora continues. "Then there is a fake-serious opening where she's singing `From a Distance,' which breaks into her current song, `I'm Beautiful, Damnit!' So there is this very celestial start and ground fog and the world revolving with the use of the lights and that appearing and then going down to sort of a funky place and the core coming apart with all the girls." The globe is preset at the top of the show and comes apart in nine pieces. "The way it fits together and is painted and lit, the sections are not readily detectable," Waldrop explains. "We finally came up with the image of a pinata breaking open and the idea that the world contained a festival. So Bob did costumes for the dancers that were reminiscent of those different festivals. The sections would be like Vegas backpacks being carried off. We'd turn it and break it. Then the idea for the oversized puppet of Bette came along and we all liked that idea." Puppets make a strong return appearance after mermaid Delores De Lago runs for president. "The puppets were a major portion of the show," deMora says. "Bonnie Erickson of Harrison/Erickson was the puppet coordinator. After the `Delores for President' scene, we decided to add a big political convention where all those supporters arrive onstage--and they're usually all celebrities. So we have 32 celebrities there." The puppets were constructed in New York by puppeteer Randy Carfagno. "We had estimates on creating new puppets from scratch and it just came in at too much money, so we went to rubber masks that were commercially available and then altered and made them more puppet-like," Waldrop explains. "We added foam-rubber hair and glass eyes, and they were all repainted. It turned out to be quite successful. We had to come at it from terms of down and dirty in terms of budget. The masks were cut and rigged, and the mouths all open and close and the heads go back and forth. The creation of those rigs was very interesting, because each dancer wears a rig that has eight heads on it. It was a way of making a big crowd onstage. We put some real people walking along next to the groups who could also break off from the groups, so you couldn't quite be sure. "We were also combining it with video elements--that's the only place in the show where we use pre-shot video of our show," Waldrop continues. "At the end of the election we have the 'We are the World' section and we wanted to get a lot of portrait shots of the puppets, because in arenas, people couldn't really see who they were. You can tell people are relying on the video, because every time a new face comes up it will get a laugh." For the rest of the show, the video is almost seamlessly integrated into the rest of the overall design. "We worked very hard with video director Monica Caston [whose credits include tours with U2 and the Rolling Stones] on a video package that was not used in its normal way but rather to produce scenic elements or provide yet another backdrop," deMora explains. "For `Lullaby in Blue,' we have a moonrise and a little house appears and smoke goes and stars twinkle. When it's used in conjunction with Allen Branton's lighting, they can both color and bleed back and forth, so you don't know where the video starts and the lighting effects stop. We also try not to use it constantly. We try to use things very carefully and selectively so they are special for that moment and not a continuous barrage of effects thrown at the audience's eyeballs." Branton and the lighting crew were asked early on to tone down the show's lighting effects. "We had some lighting going in the beginning that was a bit more what you'd call your traditional rock-show arena lighting," Branton says. "It was a little more cue-intensive and, for lack of a better term, flashy. Mark, Bob, and Toni reined us in a bit--they thought it was competing too much with the content. And they were right. If you're going to make a commitment to that sort of content and attention to detail, to obliterate it with effects and all sorts of retinal trauma from the lighting doesn't make any sense." The show relies on an essentially automated lighting system, except for the followspots and one conductor special. The equipment, supplied by VLPS, consists mainly of VL6[TM] and VL7[TM] luminaires as well as High End Systems Studio Color[R] and Studio Spot[TM] automated luminaires. "We wanted some different gobo options and High End's approach to making gobos and the kind of images they project are very different from Vari-Lite's," Branton explains. "So for variety's sake, we wanted to have them as well. PRG was the North American distributor for the Robert Juliat followspots, so John Lobel [of Light & Sound Design] brought one to me [earlier in the year] for us to try. He also brought some of the Juliat automated lekos as well--they're basically automated shutters. We all loved the light and its even field. So we specified them on the show and we're very happy with them. We have two Lycian [followspots] as well because of an availability problem."

"We weren't given a lot of time in the rehearsal process to create lighting cues, but since then, we've slowly improved it," adds lighting director Kevin Lawson. "It really is a nuance show. She's such a dynamic performer that all she needs is a couple of followspots and the audience would feel like they had gotten their money's worth. Our job is to embellish on that without distracting from her. It's refreshing and it gives a subtler feel to the show. So when we do some of the more upbeat numbers and we add a little more of the traditional flash, it's more effective." High-quality costumes--and lots of them--provide much of the show's visual splendor, deMora did the costumes with New York-based costume designer Frank Krenz. "He's very talented, so we split it up and he did certain numbers of clothes and I did others," deMora explains. "It was very much a collaborative effort, but I do more of the traditional comedic pieces, such as Delores De Lago and her girls. We keep certain pieces from tours past, but we always refurbish so it's fresh for the new show. Frank gave major input because we had 10 girls plus Bette and the three Harlettes and a lot of different changes. Krenz joined the show just as it was going into production rehearsals. "Since I had been there from the beginning, I could visualize which costumes would work best in which parts of the show," deMora explains. "I did the black-and-white coat she starts off wearing for the cover of her `Bathhouse Betty' CD, and the girls inside the world represent all the carnivals of the world. That was all designed by me. Bill Hargate, based in California, built most of the costumes and then we do a lot in-house. My assistant, Jill Focke, who was formerly head of wardrobe at the Houston Opera, has worked with me for years. She's brilliant. We rehearse for six weeks, so we have a costume shop set up. Anything not built by Bill Hargate is built by us, like the Pope and Barbra Streisand, grass skirts, and all the schtick. It's very extensive." The tour's third costume credit is Jeff Yoshida. "He did the traditional Hawaiian gown that's used during `The Rose' for the girl who comes up and interprets that song with Hawaiian movement," deMora says. "He's a Soho couturier. There are people all over the place doing things, but the whole concept is really under my aegis. It has to be controlled so it all looks like it comes from one place. It all comes from Bette and then I filter it down." deMora is most adamant about giving credit where it is due. "Tait Towers was brilliant. Michael Tait is a genius, so we were very lucky," deMora says. "We really have the `A' team, because the crew is breathtaking. The riggers who hang the 179 points--Mike Farese is up there and Mike Devlin is under the deck. They work day and night and are wonderful. This is a piece of theatre that gets set up in an arena, and I'm so finicky about how it looks. It has to look as neat as possible; it has to be a presentation. It's difficult to make it as good as you want it to be when it travels around and it has to be up and ready for sound check at 3pm every day, but those are the realities. It's so hard to surmount." While January 1 was the last scheduled show at press time, there is talk that the Divine Miss M will extendthe tour for another leg, since it's been so successful. "There is that possibility, but nothing has been said yet," deMora says. "That would be nice." While

Midler does not leave the stage without performing her big, mainstream hits, such

as "Wind Beneath My Wings," her show is full of a variety of vaudeville

gimmicks--a girl who becomes a table with a Chianti bottle on her back, dancing

doobies, singing mermaids, active volcanoes. "It's all just fun," deMora

says. "We have all those silly, fun parts from our Off Broadway days. Making

a volcano out of a Ribbonlift and stretch velvet is about as silly and as low

tech as you can go, but it's what we're about. It's not to spend tons of money

on effects. We don't need effects; we have her. She is the effect!" Bette Midler's Divine Miss Millennium tour Production supervisor Mark Waldrop Choreographer Toni Basil Production design Robert deMora Costume design Robert deMora, Frank Krenz, Jeff Yoshida Lighting designer Allen Branton Production manager John "Bugzee" Hougdahl Show stage manager David O'Brien Production assistant Michelle Esmonde Lighting director Kevin Lawson Lighting board operator Chris Nyfield Project supervisor Wayne Boehning Lighting programmer Victor Fable Lighting crew chief Clay Brakeley Lighting technicians Greg Kocurek Candida Boggs Greg Gore Lead wardrobe Jill Focke Assistant wardrobe Nicole Kuhns Carpenters John Kinal Michael Devlin Greg Gish Chris Roberts Head rigger Michael Farese Rigger Kevin McDonnell Props Chris Malta Seanne Farmer Melanie Philips Video director Monica Caston Video engineer Zainool Hamid Video projection Jeff Crane Camera operators Tom Fenno Michael Goulding Michael Miller FOH sound engineer David Morgan Monitor engineer Glen Collett Sound technicians Matt Herr Mike Bodan Eugene Philips Pyrotechnics Mike Kinard Video BCC Video Sound Clair Bros. Audio Staging Tait Towers, Inc. Main lighting contractor Vari-Lite Production Services |

Always

a Sure Bette.(Bette Midler)

Always

a Sure Bette.(Bette Midler)  k

at clocks and astrological charts. They also stopped in at the Lincoln Center

Performing Arts Library to look at tapes of different performance artists and

puppeteers. "We were very interested in doing something that would be a little

more abstract than most of the tours on the road," deMora says. "We

started off talking about doing the show in the round, but that seemed impossible

as far as Bette's performing. Singing is fine, and for a band [it's fine], but

she also tells jokes. And you can't land a joke very well if the audience, or

a large part of it, is behind you. Plus, she's very fond of proscenium--she likes

a proper stage."

k

at clocks and astrological charts. They also stopped in at the Lincoln Center

Performing Arts Library to look at tapes of different performance artists and

puppeteers. "We were very interested in doing something that would be a little

more abstract than most of the tours on the road," deMora says. "We

started off talking about doing the show in the round, but that seemed impossible

as far as Bette's performing. Singing is fine, and for a band [it's fine], but

she also tells jokes. And you can't land a joke very well if the audience, or

a large part of it, is behind you. Plus, she's very fond of proscenium--she likes

a proper stage."  Much

effort went into creating the perfect effect for the volcano, which closes Act

One. "Obviously, the button of the act had to be the volcano erupting,"

Waldrop says. "We had talked about putting pyro up on the lift and keeping

Bette down on the stage so we could have a real pyro explosion at the end of the

act. But then Bette decided that she wanted to be on top of the volcano--which

is a very Bette-like thing to do--and she was absolutely right. Still, that created

a problem, because then we couldn't put the pyro on top. So we talked about moving

in some pyro behind once the mountain went up, and we had a lot of demos with

the pyro people and a lot of going back and forth. It would have been tremendously

expensive. Finally, our production manager, Bugzee, grabbed a CO2 fire extinguisher

at a demo and just squeezed it, emitting a great plume of white steam. We probably

saved Miss Midler about $100,000 and it works just as well. It's the perfect effect.

The guy who puts the feather mask on her head just walks out--we made a little

rattan slipcover for the fire extinguisher so it kind of blends into the decor--and

he carries it out in full view. As soon as the mountain goes up, he sets it off.

It couldn't be cheaper."

Much

effort went into creating the perfect effect for the volcano, which closes Act

One. "Obviously, the button of the act had to be the volcano erupting,"

Waldrop says. "We had talked about putting pyro up on the lift and keeping

Bette down on the stage so we could have a real pyro explosion at the end of the

act. But then Bette decided that she wanted to be on top of the volcano--which

is a very Bette-like thing to do--and she was absolutely right. Still, that created

a problem, because then we couldn't put the pyro on top. So we talked about moving

in some pyro behind once the mountain went up, and we had a lot of demos with

the pyro people and a lot of going back and forth. It would have been tremendously

expensive. Finally, our production manager, Bugzee, grabbed a CO2 fire extinguisher

at a demo and just squeezed it, emitting a great plume of white steam. We probably

saved Miss Midler about $100,000 and it works just as well. It's the perfect effect.

The guy who puts the feather mask on her head just walks out--we made a little

rattan slipcover for the fire extinguisher so it kind of blends into the decor--and

he carries it out in full view. As soon as the mountain goes up, he sets it off.

It couldn't be cheaper."  Because

Midler didn't completely set the show until the last minute--the first run-through

was opening in Boston--lighting cues had to be added after the tour began. "When

you do a Broadway type of show, the details really motivate the lighting and vice

versa," Branton says.

Because

Midler didn't completely set the show until the last minute--the first run-through

was opening in Boston--lighting cues had to be added after the tour began. "When

you do a Broadway type of show, the details really motivate the lighting and vice

versa," Branton says.