Mister D: Remember that unflattering review about Zellwegger looking like a bloated Bette Midler in Chicago….NOT!!!….well, whatever…it never set well with me…this is an interesting article and I was glad to hear at some point Bette was considered for the part. In recent pics at the premiere of Chicago, I thought Ms. Zellwegger even resembled Bette cicra the days of For the Boys Can’t wait to see the movie, though…

Cut to a Broadway rehearsal hall, 1974.

Gwen Verdon had waited some 20 years to play Roxie Hart, a philandering Chicago housewife who goes on to notoriety and show-biz fame after killing her lover. It was in the mid-1950s that Verdon, who had assayed a variety of fallen women in such shows as “Damn Yankees,” “Sweet Charity” and “New Girl in Town,” saw musical potential in the 1942 Ginger Rogers movie “Roxie Hart.” But the agile dancer would stumble trying to acquire the rights to the movie’ s source, a 1926 Broadway play called “Chicago.”

The obstacle was Maurine Dallas Watkins, a washed-up Hollywood screenwriter who had reached the summit of her achievements with the play (and a subsequent film version in 1928). A trenchant satire of legal grandstanding and yellow journalism that scooped “The Front Page” by two years, “Chicago” emerged from Watkins’ days covering the sensational Leopold-Loeb trial and sundry murder cases for the Chicago Tribune.

The characters Roxie and Velma were patterned after Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner, two Cook County jail murderesses who achieved a local celebrity thanks to Watkins’ tart columns. Watkins, feeling complicitous in the two women’s acquittals, sat on the play.

“She felt she had done enough damage already,” says Martin Richards, producer of the musical’s 1975 production and the new film version. After Watkins died in 1969, Verdon bought the rights. It would take another five years before her husband, Bob Fosse, would enlist his “Cabaret” composer-librettist team of Kander and Ebb. They would conceive it as a musical vaudeville, with numbers modeled after great performers of that show- biz heyday: “Mr. Cellophane” was black showman Bert Williams, “When You’ re Good to Mama” was Sophie Tucker and “Funny Honey,” Helen Morgan.

But the waiting had just begun. Chita Rivera, the original Velma, clearly remembers that fateful second day of rehearsals.

“We went through the script and broke for lunch,” recounts Rivera. “I remember seeing Gwen sitting there knitting for the courtroom scene. Then the climate of the room changed. There was speed and energy, and they whisked her off. That was when Bob had obviously been rushed to the hospital with a heart attack.”

The show was suspended for three months, and the “Chicago” director would later get mileage from his hospital ordeal in his self-referential film “All That Jazz.” But the Fosse who returned three months later was a morbid Fosse, and the show became increasingly darker and more risque.

“‘Roxie Hart Has No Heart,'” quotes Richards from one of the out- of-town reviews. Fosse would tone down the show to a degree prior to Broadway, abetted by script additions from friends Paddy Chayevsky and Herb Gardner. At least one of Chayevsky’s lines (when lawyer Billy Flynn claims: “If Jesus Christ had lived in Chicago today…and come to me, things would have turned out differently”) would be retained by screenwriter Bill Condon.

But “Chicago,” docking in New York a week and a half after “A Chorus Line,” was met with a mixed response. Among the many who loved the show, however, was a movie-struck young man in his early 20s named Harvey Weinstein.

Cut to Miramax offices, lower Manhattan, May 2000.

Rob Marshall walked in the door for one movie, and walked out with another.

The genial Midwestern-bred choreographer had a meeting with Miramax executive Meryl Posterto discuss a possible movie of “Rent.” Barely 40, he was heating up in movie circles after staging the dances for the hit Sam Mendes revival of “Cabaret” on Broadway and reconceiving “Annie” for network TV.

Marshall recalls: “I said, ‘Before we begin jumping into the whole “Rent” thing, can I just tell you what I would do with “Chicago”?'”

It was a measure of Marshall’s confidence that he felt he could crack a nut that had humbled Fosse (who told Kander and Ebb he had the solution, then died before revealing it), that had eluded Martin Scorsese (who had been approached by Ebb and Liza Minnelli during “New York, New York”) and that had chastened Nicholas Hytner (who left the project after giving it a serious shot). Writers from Larry Gelbart to Wendy Wasserstein had come and gone in the process. Marshall was undeterred.

“Within minutes she dragged me into Harvey Weinstein’s office. I was actually up on my feet doing some moves, trying to explain the big conceptual idea: that it would live in two different worlds, this world of fantasy vaudeville and the reality world of Chicago of the time. I think it was confusing to Harvey, , but exciting at the same time. I think that he realized that the score was written in a way that doesn’t work outside the theater, because they’re not the usual book songs where people just sing to each other.”

But “Chicago” screenwriter Condon, an Oscar winner for “Gods and Monsters,” also felt the traditional approach to segueing into song had defeated earlier versions. “It seemed odd that all the other attempts had been to do it straight. In one unused screenplay, you’d have Roxie arrested, and the reporters calling in the story would start to sing, ‘The name on everybody’ s lips is going to be Roxie.’ And then she’d sing back, and the cops would join in, and by time she got to prison, the prisoners would join in…”

Marshall and Condon found their device with the help of such movies as “Pennies From Heaven,” “The Purple Rose of Cairo” and Fellini’s “Variety Lights,” films in which characters express their dreams through the fantasy of song, movies and stage. With Roxie as their dreamer, the pair would create a narrative that would allow for the simultaneous performance of a song in Roxie’s fantasy world (the vaudeville stage) and her real world (the prison). Another prototype could be found in the film of “Cabaret” by Fosse, whose stylistic imprimatur Marshall would have to overcome once again.

“I’ve had to do that on stage several times, with ‘Cabaret,’ ‘Little Me’ and ‘Damn Yankees,'” says Marshall, who completely rechoreographed “Chicago.” “I think the man is a genius and a hero. But for me, the way of dealing with that is to reconceptualize [the material] in a way that doesn’t lead me down the same path.”

In one of Marshall’s more memorable inventions, the dummy-and- ventriloquist act of Roxie and her lawyer, Billy Flynn, in “We Both Reached for the Gun” is accompanied by a chorus of marionette reporters. In “Cell Block Tango, ” Marshall enhances the production number frisson by having the convicted women tango with their victims.

The biggest problem child, Marshall admits, was Flynn’s “Follies” -style paean to courtroom soft soap, “Razzle Dazzle.” “That one took the longest. We rethought it and rewrote it on the spot. I realized very late that we couldn’t do a number without folding the story into it. Otherwise, it just sits there in the show as a wonderful spectacle.”

“This movie is all about Rob Marshall, as far as I’m concerned, ” says “Chicago” composer Kander, who with Ebb wrote a new tune (“I Move On”) to be sung over the closing credits.

Perhaps Marshall’s cleverest feat of problem solving was in locating audition-allergic stars who could sing and dance. Zeta-Jones first signed as Velma, a role that had at various times been linked with Minnelli, Madonna (Fosse’s idea), Jennifer Lopez and Nicole Kidman. A former musical- comedy performer who played Peggy Sawyer in an earlier West End production of “42nd Street,” Zeta-Jones was “discovered” performing at a party by Martin Richards and subsequently observed on videotape by Marshall doing a Kurt Weill number at an awards presentation.

For Billy Flynn, Richards had wanted Kevin Kline, whom he had helped make a star in his Broadway production of “On the 20th Century.” But Kline felt he had bigger fish to fry, as did Kevin Spacey, Hugh Jackman and John Travolta. Marshall eventually agreed on Richard Gere, whose musical savoir faire had been demonstrated in “The Cotton Club” and a London production of “Grease.”

Producer Richards lost his preferred Mama Morton (Kathy Bates) to Weinstein’s pick (Queen Latifah) after Judi Dench failed to materialize. Other essential parts were filled by John C. Reilly, as Roxie’s milquetoast husband, and Christine Baranski, as reporter Mary Sunshine after the character (played onstage as a vaudeville-inspired drag act) underwent a sex-change operation necessitated by the realistic glare of the camera.

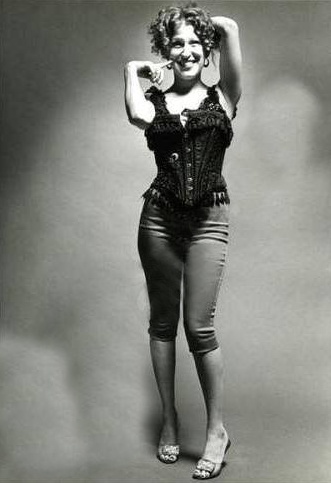

The hardest casting would be Roxie, who had at various times been connected to Goldie Hawn, Bette Midler, Charlize Theron and Gwyneth Paltrow. “We did the whole Scarlett O’Hara search,” says Marshall. “I basically made it a blanket rule that if you’re interested in the role, you have to come in for a work session.”

Marshall saw more than a dozen big-name actresses before an initially stand-offish Renée Zellweger appeared. “She came in to watch us dance a little, and after the meeting broke up and everyone left she grabbed me, shut the door and said, ‘Show me that one step you were working on.’ She dipped her toe in very gingerly, and I started working with her. She was a former gymnast, cheerleader and runner, so she picked it up with style.

“Later on, we were sitting at a restaurant at the Four Seasons Hotel, and she said, ‘What’s that song Roxie sings at the end?’ I started singing ‘Nowadays’ to her, and she started singing. And then some more. It was kind of embarrassing, but at least I got to hear if she could sing.”

Rivera, who would do an honorary cameo, gave her seal of approval. “The part is so difficult because you really have to have somebody that seems like she can do no wrong. And she’s the worst – she’s a murderess. Gwen could do bumps and grinds, and you could go, ‘Oh, isn’t that cute? Isn’t that just the sexiest thing you’ve ever seen?’ Goldie Hawn has that quality. And Renée has that quality. When I saw a picture of her on the piano singing ‘Funny Honey’… I thought, there it is.”

Cut to a rehearsal hall in Toronto, November 2001.

Before they tell you anything else, everyone connected with “Chicago” will tell you that everyone is really doing what you are seeing them do. But before they did it, they had to undergo a rigorous rehearsal period.

“We rehearsed for those six weeks like I’ve never rehearsed in my life,” admits Marshall, who, among other pressures, had to justify a $51- million budget for his first feature film. “We had four rooms going at the same time. It was like school: You had your singing, your dancing, your scene work. We were moving from place to place so quickly it must have felt like it felt like in the old times of Arthur Freed’s unit at MGM, with musicals happening in every room.”

“I’m glad he came from Broadway,” says Latifah. “Because he’s used to running and drilling and rehearsing. He was rock steady. He never lost his cool. You wanted to come through for this guy.”

Latifah credits Marshall with balancing a strong vision with a collaborative openness: what Marshall describes as “whoever has the best idea wins.” Latifah, a kinder, gentler Mama Morton, resisted the character’ s chief vaudeville influence. “The music coach would say, ‘Sophie Tucker did this and Sophie Tucker did that.’ I kinda didn’t want to know what Sophie Tucker did. I’m a 30s black girl, you know what I mean? I wasn’t going to be that. I wanted to just bring what I bring to it.”

For his “Mr. Cellophane” number, Reilly recalls the director telling him to just “‘start moving around and I’ll just throw in my ideas here and there.’ That way he got really organic performances out of everybody, because you were doing movements that felt right to you.”

For Gere, who had to learn tap-dancing from scratch, the training period was “incredibly humiliating and painful. Because of the physicality of it and the concentration, I’d be in a flop sweat in five minutes. I got very shy about it. I didn’t want anyone to see this horrendous process. It took several months before even the beginnings of it being natural, when the feet were just doing it on their own.”

No one was more driven, perhaps, than Zeta-Jones. Deliberately saving her virtuosic solo “I Can’t Do It Alone” for last, Zeta-Jones asked for retake after retake.

“I got to the point where my legs were like jelly,” she recalls. “I kept saying to Rob, ‘I have to do it again.’ In a way, I didn’t want them to say, OK, it’s a wrap. It’s the classic actor syndrome, when you’re driving home and you suddenly understand what it was you were struggling with. After I went home I relived and redid everything in my mind.”

Zeta-Jones’ thoroughness would strike an 11th-hour note of dissonance as she watched her role being whittled down in rough cuts. With two of Velma’s numbers already excluded from Condon’s screenplay and the Velma-Mama Morton duet “Class” reluctantly dropped after the last test screening (it was perceived as slowing the film down), the film’s balance sheet dipped toward Roxie. Zeta-Jones made noise, and two of her numbers were recut in her favor.

“Shocking diva stuff,” recounts one witness, who said it came as a surprise because the actress was a trouper throughout. “She kind of loved getting into the gypsy thing and was actually generous with Renée, because Renée had to catch up.”

Marshall, true to form, remains sanguine about the incident. ” I love collaborations, and I really wanted their feedback. I was struggling with the balance constantly. And she pointed out something that was so valid to me. So it was a very healthy thing.”

Cut to New York City, 2002: Fred Ebb on the ground.

When “Chicago” opens it will be 76 years, almost to the day, that Watkins’ play opened on Broadway, and 27 years since Fosse launched the musical. At least one person who wondered if the movie would ever happen was Ebb. “After a while,” he says, “you just sit back, read a book and wait to see what is going to happen.”

Ebb is happy because Condon restored a line of dialogue he was particularly fond of. It belongs to Roxie: “I’m gonna tell you the truth. Not that the truth really matters, but I’m gonna tell you anyway.”

The line epitomizes the sourball outlook of a piece that seems to have found its moment. “Time has caught up with the show,” says Ebb wistfully. “It’s the climate of the country. We shocked a lot of people who found us bitter and relentless. Now our sarcastic and sardonic view of the country is something many people share. I mean, it’s sad, and I’m not happy about it. But I’m proud of the fact that we saw something. Now a lot of people say, ‘Hey, you know, you were right. It’s out there. Whatever you were telling us is out there. It really is.'”

Jan Stuart, It’s About Crime / It was murder getting ‘Chicago’ to the big screen: three decades of holdups, talent troubles and …all that jazz. , Newsday, 12-20-2002, pp D06.