Mister D: I know this is an extremely long article, but Mr. Mardin is responsible for some of the best charts and production of many of Bette’s albums, including the songs “From A Distance” and “Wind Beneath My Wings”. Those were just the award winning songs, too. Anyway, I think it’s just good manners to acknowledge the people who helped Ms. Midler along the way… and this is a great article on the history of Mr. Mardin…wish him luck tonight….

By Richard Harrington

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, February 23, 2003; Page G01

Arif Mardin, the veteran record producer, got the call in August 2001. Bruce Lundvall, head of Blue Note Records, had signed a gifted young singer and had recorded her debut album with another producer.

Arif Mardin, the veteran record producer, got the call in August 2001. Bruce Lundvall, head of Blue Note Records, had signed a gifted young singer and had recorded her debut album with another producer.

“Bruce said, ‘I’m not happy with it, so just go ahead and re-record the album,’ ” Mardin recalls. “In a very pleasant three weeks, the album was finished and we said, you know, it’s a nice album, but it doesn’t sound like it’s radio-friendly. So we’ll just have to concentrate on the second CD, though we’re very proud of this one.”

The album was released in March, to the slow sales Mardin had feared.

“And all of a sudden,” Mardin notes, “the media started, and all the positive raving, the glowing reviews, exposure on National Public Radio, led to appearances on morning television and more sales, then the evening shows with Letterman and Leno, and that drove sales, and the avalanche started. It looks like people were ready for heartfelt, honest music.”

What people were ready for was Norah Jones’s “Come Away With Me,” the leftest of left-field hits: It has sold 4 million copies stateside and 2 million overseas. At tonight’s Grammy Awards, “Come Away With Me” is nominated for album of the year, its hit single “Don’t Know Why” is up for both record and song of the year, and Jones, 22, is up for best new artist.

And at age 71, Arif Mardin finds himself nominated for producer of the year, an award he first won in 1975. A win over Dr. Dre, Rick Rubin, Nellee Hooper and Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis would bring Mardin his seventh Grammy overall. The odds may be in his favor, since Mardin, whose career stretches back 40 years, is clearly respected by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. NARAS inducted Mardin into its Hall of Fame in 1990 and, just two years ago, gave him the prestigious Trustee Award for a lifetime of achievement in music, putting him in an elite group of producers and composers that includes George Martin, Phil Spector and Quincy Jones, who actually seeded Mardin’s career (more on that later).

The multi-platinum sales figures and the wealth of Grammy nominations are remarkable results for “Come Away,” a low-key, acoustic-focused collection of jazz- and blues-tinged pop songs by a brand-new artist. And unexpected ones, since Lundvall had belatedly hooked Jones up with Mardin, who had just joined the Blue Note subsidiary Manhattan after a 36-year career at Atlantic Records.

“In my mind, Arif was always one of the consummate producers and arrangers,” says Lundvall. “He’d done everything from jazz artists, to Aretha Franklin and Dusty Springfield, to the Bee Gees and the Rascals, and [the original-cast recordings for] Broadway shows like ‘Rent’ and ‘Smokey Joe’s Cafe’ — every kind of music. I was just so lucky that he now worked here.”

Jones had already cut an album with producer Craig Street, best known for his work with Cassandra Wilson, but Lundvall thought it too busy and cluttered, not focused on Jones’s gorgeously sultry voice and spare piano. The airy sound of Jones’s demos and live performances, the very thing everyone at the label had fallen in love with, was nowhere to be found.

“So I went to Norah and said, ‘Look, I’ve got the greatest producer in the entire world here on staff and I’d like you to meet with him.’ ”

“Arif came in pretty late in the game,” Jones recalls. “I knew his name but I wasn’t quite sure, so I checked him out, and he’d produced every favorite record in my collection! Then I was a little bit freaked. I loved Arif’s work, but I was really nervous, because I didn’t want a lot of production and I didn’t know what he wanted to do.

“I asked if it was okay if I used my musicians, and he said fine, and then I wasn’t really worried. . . . We’re a subtle band as it is, so Arif came in and just sort of finessed it and did a really good job of respecting what I wanted while still doing his job and getting me to where I should have been.

“Isn’t he great!”

When Mardin joined the Manhattan label, he told Billboard magazine he was “looking for crossing-over, young artists. It’s great to be able to work on different ideas and concepts, but still be commercial, [though] I won’t be chasing strict pop formulas. . . . ”

“I don’t take a project if it’s just a crass commercial project with no musical value,” Mardin adds. “This one was totally the opposite: total honesty, total heartfelt music. No electronics, no pitch correction, nothing, just four or five people playing together. It reminded me of the grooves we used to get in the studio with musicians in the ’60s and ’70s at Atlantic.”

Arif Mardin’s remarkable journey starts not at Atlantic but across the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean: He was born in Turkey in 1932, into a renowned family that produced statesmen, diplomats and business leaders. He might well have followed that path — he attended the London School of Economics — but for the fact that he’d fallen in love with American music at a very early age.

“We didn’t listen to Turkish music at home,” Mardin recalls. “My sisters used to listen to American pop of the day, which was big bands — Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington — and some of the crooners like Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby. This was the late ’30s. I acquired the love of jazz through them and then I became a jazz fanatic, mostly bebop and the avant-garde of the day, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. And that led to my friendship with Quincy Jones, who came to Istanbul with Dizzy’s orchestra.”

“We didn’t listen to Turkish music at home,” Mardin recalls. “My sisters used to listen to American pop of the day, which was big bands — Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington — and some of the crooners like Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby. This was the late ’30s. I acquired the love of jazz through them and then I became a jazz fanatic, mostly bebop and the avant-garde of the day, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. And that led to my friendship with Quincy Jones, who came to Istanbul with Dizzy’s orchestra.”

The year was 1956, and Gillespie’s band, with Jones as arranger, was touring the Middle East under the auspices of the U.S. Information Agency. The young Mardin had been composing and arranging original material — “I knew how to orchestrate but it was all done in a haphazard way” — and he summoned the courage to show his work to the visitors.

“I had a work in progress and I took it to Dizzy when he was rehearsing for his concert, and he took the time to play it — I was amazed — and he gave me pointers. Some of my other pieces Quincy sent to the Berklee College of Music in Boston and said, ‘This is the guy I want to give the first Quincy Jones Scholarship.’ ” It was at Berklee, Mardin notes, that he “formalized all that self-collected knowledge,” studying harmony, counterpoint, composition and orchestration. He graduated in 1961 and taught at Berklee for a year before forging a particularly rich alliance with Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun.

The sons of Turkey’s ambassador to the United States, also lovers of American jazz and rhythm and blues, had started Atlantic Records in 1954. Nesuhi Ertegun, who headed the jazz division, offered Mardin a job as his assistant and studio manager, then elevated him to “supervisor,” which included some arranging and production.

“I used to produce jazz records, but that was so easy,” Mardin explains. “People play a good solo and you say, ‘All right, that’s the take!’ There was no changing, no editing; you would do a song until you had good soloing.”

In music, the producer’s role is a combination of the film world’s producer and director responsibilities: gathering the musicians for the recording sessions, making musical suggestions to enhance their performance (and sometimes shaping the repertoire), giving the engineer recommendations for sound balance and effects. Producers, whether hired by the artists or the labels, differ sharply in how they approach the job. Mardin, for instance, looks for ways to underscore the music rather than overshadow it; sometimes it’s as simple a matter as shifting a song to a more comfortable key or adding subtle countermelodies. And four decades of experience crafting on-the-spot arrangements come into play as well, particularly since Mardin prefers the end results to be achieved live in the studio, rather than tweaked via technology after the fact.

“Nesuhi was the first to discover Arif’s gifts,” says Ahmet Ertegun, CEO of Atlantic and one of the most respected and beloved figures in the music business. “When we discovered that we had a great arranging talent in-house, myself and Jerry Wexler” — the producer and Atlantic’s co-founder — “availed ourselves of his services.”

“I learned to mix records from the late [engineer] Tom Dowd, my mentor,” Mardin points out. “Then Jerry and Ahmet gave me my first production job with Tom — we were assigned to the Young Rascals. That first record was ‘Good Lovin’,’ which went to Number 1, so jazz went to the back burner at that time.”

That was 1966. A year later, Mardin’s stock rose with Aretha Franklin’s arrival at Atlantic after she’d languished for several years at Columbia. At Atlantic, Franklin met up with the A-team of Wexler, Dowd and Mardin. “We all worked together at all the important sessions,” Mardin remembers. “We usually had one lead person, but all the others were supporting.”

For instance, Mardin did the arrangements on Franklin’s commercial and artistic breakthrough, the masterpiece soul album “I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You,” which included the classic “Respect.” In her autobiography, Franklin calls Mardin “a musician’s musician; whether it was horn charts or string charts, Arif had the magic touch, illustrious arrangements of depth and beauty.”

The team would be responsible for such classic Aretha albums as “Lady Soul,” “Spirit in the Dark,” “Amazing Grace,” “Young, Gifted and Black” and “Soul ’69,” the mis-titled jazz album that Mardin arranged and conducted. The late ’60s also brought Dusty Springfield’s classic “Dusty in Memphis.”

The ’70s were extremely busy — and wide-ranging — for Mardin. Among his solo productions were John Prine’s acclaimed self-titled debut album; Hall & Oates’s first two albums; Chaka Khan; Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack; King Curtis; and the Average White Band, notably its blue-eyed-funk classic “Pick Up the Pieces.”

That decade will probably be best remembered for Mardin’s resuscitation of the Bee Gees’ career. By 1974, the Bee Gees were drowning in ballads, struggling to recapture their late-’60s pop success, when manager Robert Stigwood sent them to Mardin looking to charge their sound with an infusion of the American R&B they loved. The first album, “Mr. Natural,” was a step in that direction; 1975’s “Main Course” heralded the arrival not only of the new Bee Gees but also of the commercial disco era, thanks to the monster singles “Jive Talkin’ ” and “Nights on Broadway,” the first Bee Gees song to feature Barry Gibb’s signature falsetto.

Blame it on Mardin: While recording “Nights on Broadway,” Mardin suggested that Gibb attempt to sing the melody one octave higher. “Barry just tried to oblige me but said, ‘If I sing in full voice, I’m going to sound like a fool.’ So he tried falsetto and that became one of our trademarks,” says Mardin.

The ’80s brought such chart-toppers as Chaka Khan’s “I Feel for You,” Bette Midler’s “Wind Beneath My Wings” and “From a Distance,” Phil Collins’s “Against All Odds” and a host of album projects, including Aretha Franklin’s comeback albums when she moved from Atlantic to Arista. Though he’d become a senior vice president at Atlantic, Mardin was always free to produce anywhere he wanted, as with Barbra Streisand’s 1997 Columbia album, “Higher Ground.”

Two things are apparent in Mardin’s discography: Unlike many producers, he doesn’t have a signature sound, a thumbprint to easily identify his work. And he seems particularly sympathetic to women.

“There are many producers out there, who will go unnamed, who end up making records that sound like their records, rather than the artists’,” says Lundvall. “They have a signature sound and you go, ‘Oh, that’s another record produced by X.’ Not in Arif’s case — everything he does serves the artist.”

As Mardin sees it: “In the old days, someone like Phil Spector had a certain sound, and different artists that he used would be featured within that soundscape, and they were great. I’d usually go with featuring the artist, build the arrangements around the artist. I didn’t want to bring the artist into a preset situation. I guess that’s why I was able to work with various artists of different styles.”

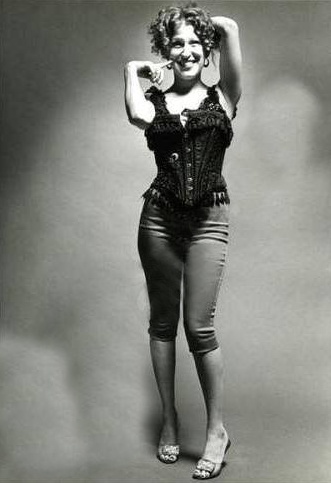

As for his affinity for women, Mardin notes: “My wife has asked that same question — why are you working with women all the time? Maybe I get along with female artists, though I have lifelong friends like the Bee Gees and Phil Collins and AWB. But the percentage of female artists is higher. Maybe it’s just a matter of me being lucky to be connected with great singers like Norah, Aretha, Bette.”

Lundvall has another take. “A lot of women performers are intimidated by strong-willed producers,” he suggests, chauvinists whose attitude is “this is what I want, this is how it’s going to be.’

“Arif has his secret way of getting his way while letting the artist assume that they’re getting their way. He’ll make suggestions — why don’t you just try it in a different key, just try it, I think you’ll like it. . . .

“That’s what happened with Norah. Arif came up with lots of subtle touches, like the violin on ‘I’ve Got to See You Again’ and ‘One Flight Down,’ the sustain organ on ‘Turn Me On,’ doubling Norah’s voice, which she hadn’t thought of. She has great pitch, so she’s in perfect harmony with herself, which is one of the things that amazed Arif about her: It was all in one take, practically.”

Ahmet Ertegun notes that Mardin “has a terrific background as a musician, and a great understanding of the capabilities of the people that he works with, and he’s able to maximize and bring about the magic when they perform a song by putting it in the correct atmosphere. He certainly did that with Norah Jones.”

That Mardin was available to do so says something about the contemporary music business. As part of the AOL Time Warner merger, Atlantic retired everyone older than 55, including Mardin and his longtime business partner, Ian Ralfini. According to Lundvall, who met them at lunch soon after, “Arif was so depressed because all he wanted was his office, and he’d been with Atlantic 39 years.”

Lundvall had started Manhattan in 1984 as a pop label, but it had been dormant for a decade. “But we still owned the logo and trademark, so we reformed as a boutique adult pop label and asked if [Mardin and Ralfini] were interested,” he recalls. “We were worried about affording them, but they said, ‘It’s not about money, we’re okay that way, we just want to work.’ I’m 67, Arif is 71, Ian is 62, so I said we’ll install some wheelchair access around here and we’ll all have a great time.”

“Come Away With Me” was released Feb. 26. “No one was counting on what happened,” Lundvall admits. “But when the record was done, I couldn’t stop humming the songs and hearing her voice in my head — the secret was, that voice and those songs penetrate. Arif focused beautifully on the beauty of Norah’s voice and piano playing.”

Tonight, Arif Mardin, who has already added to his total of 40 gold and platinum albums, may have to find shelf space for another Grammy or two. In a few months, he and Jones will start planning the follow-up, though “Come Away With Me” shows no sign of burning out: It recently spent a few weeks at No. 1 on the album charts, nine months after release. There’s no hurry.

© 2003 The Washington Post Company