Behold the merry wives of Stepford

By LYNN CROSBIE

From Saturday’s Globe and Mail

Photo: Paramount (Thanks for sending this Sara)

Film remakes generally speak to cultural nostalgia, and desire. Every time that An Affair to Remember is remade, you can almost hear the collective sigh of women yearning for a time when romantic, gallant men fell in love, not drunkenly into your bed with a pack of Trojans and a handful of lies. Conversely, the remaking of The Planet of the Apes reflected a longing for a time in which the scariest thing we could all think of was encountering an army of well-groomed apes with British accents.

The forthcoming remake of The Stepford Wives is harder to fathom: a curious precursor to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the film and the novel constructed nostalgia as a dangerous, ill-advised sentiment.

When Ira Levin published The Stepford Wives in 1972, he established himself as one of the most militant feminists at large, his writing matched only by Valerie Solanas’s homicidal fantasy, the SCUM Manifesto.

Second-wave feminists were threatening to men for more reasons than one: Their heroic striving for gender parity in the home, the workplace and the law challenged and changed male domination forever.

And their radical ideas about female victims and male aggressors ultimately hindered everyone; binary thinking, in its most extreme form, is falsely divisive and always erroneous. When someone like Andrea Dworkin, for example, declared that rape was exclusively a women’s issue, she neglected to consider how many boys and men are also victims of this crime; forgot that women may also be capable sexual offenders.

Still, with Stepford and Rosemary’s Baby under his belt, Levin emerged from the women’s-liberation movement as its least acknowledged and most popular spokesperson. While political women of his era were routinely referred to as hairy-legged “man haters,” Levin was the most hirsute and misandronous of the lot.

Conceived of by a man capable of envisioning a queue of test tubes containing embryonic Hitlers, The Stepford Wives speaks to the author’s horror of technology (at this time best evidenced in Disneyland’s animatronic presidents), and to his deep-seated belief that normal men are capable of paranormal acts of violence against women.

In the book and film, three women — a career gal, a slob and a lazy babe with no desire for her husband — are changed by the small town of Stepford into Pledge-addicted homemakers, and perfect wives and mothers. Their breasts are all augmented in the process, and this transformation is effected by the local men’s club, a group of mild-mannered thugs who murder the townswomen and replace them with robots.

In spite of the outlandishness of this premise, both the book and movie were enormously successful, and Levin, to the best of my knowledge, was never taken to task for his paranoid, if not deranged, ideas about masculine imperatives.

Paul Rudnick is the new Stepford Wives screenwriter, and, given his mildly cynical appreciation of all things camp, from Jacqueline Susann to The Addams Family, I imagine he will twist the premise enough to reveal its fantastical hysteria.

Yet it is doubtful he will he be able to out-camp the outstanding TV sequel, The Revenge of the Stepford Wives, which featured a maniacal Julie Kavner de-robotizing in the middle of a picnic, and shedding the Stepford gals’ signature bonnet and daygown while howling for revenge.

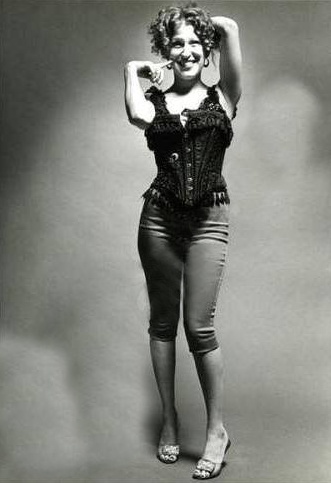

The new movie’s trailer is more creepy than ironic, and it appears that the sequel will stick to its first principles. Matthew Broderick, who plays Nicole Kidman’s husband, is seen, in the manner of Tom Cruise, plaintively telling her that she does everything better than him. In another scene, Bette Midler transforms from a dour frump into a domestic goddess, an incredible transformation under any circumstance.

The Stepford Wives appeared at a time when women were assaulting conventional ideas about femininity, including their appearance and disposition, and were expressing their disinclination to rock a squalling infant while washing the floor with strap-on foot sponges.

Arguably, we still occupy a culture that is obsessed with a specific model of female beauty, that is still Windexing the glass ceiling, and that continues to laugh at the very idea of a househusband, the comic strip Adam@Home notwithstanding.

But we also, thankfully, live in a culture that has ceased to assign blame to some shadily defined patriarchy, or to a media once thought to control our choices. “The Maybelline ad made me do it” argument has long passed, and it would behoove women to accept that certain of our excesses — from shoe worship to fun with Botox — arise from a female malady that includes competitiveness, vanity, and best of all, a love of useless luxury.

The Stepford Wives has nothing to tell us about men, then or now, but is loaded with information for women. The women in the book placidly accept their relocation to what is obviously a scarier place than Three Mile Island. They are unruffled when their husbands take to masturbating beside them and having their friends tape, draw and study them. And they live next door to robots without noticing. Has anyone ever gone to Disneyland and screamed, “I thought you were dead!” upon viewing Abraham Lincoln?

Ultimately, the film and book are an abhorrent object lesson in female stupidity and weakness, one which should have left audiences laughing harder than Charlton Heston’s “Damn, dirty apes!” speech.

Those who are still not laughing had better wise up. The feminist slogan of the 1960s was “Know your enemy.” The victim we occasionally perceive in all of us is our enemy, and it’s time we went Kavner on her ass.