Mister D: Thank you Barbara and Jason for sending this in….

NY Daily News

Divinity

Bette of the baths

By SHANTI GOLD

June 14, 2004

Bette Midler really knew how to throw a party. And the timing was good, too, since the 1960s had ended with a wicked cultural letdown.

Within a few short months, the idyllic rapture of Woodstock was shattered by the chaos of Altamont. In New York, meanwhile, a new movement was just under way: The police had raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular Greenwich Village gay bar, and the crowd had fought back and the resistance had spilled into the streets. Protests continued for days. The struggle for gay liberation had begun.

Standing at this crossroads was Bette Midler – a young, outrageous, loudmouthed, ethnic-looking Jewish woman – who seized the opportunity to throw a shindig of her own. The venue was the Continental Baths in the basement of the Ansonia Hotel at Broadway and 72nd St.

And her guests were half-naked gay men who exchanged their clothes for a towel, or less, and left their inhibitions at the door.

Bette was the perfect hostess. And the celebration was, as she liked to say, hot.

The owner of the Continental discovered Midler belting out her frustrations alongside other aspiring artists in 1970 at a nightclub called the Improvisation and offered her a job on the spot. She was bored and discouraged by a three-year run in a supporting role in “Fiddler on the Roof” that increasingly seemed to be leading nowhere. She could use the Continental’s $50 a night.

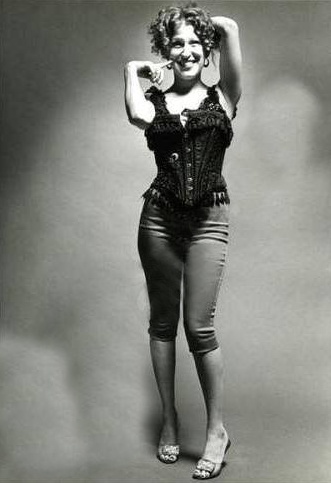

Onto the stage she strode, a 5-foot-1 firecracker with a shocking mass of frizzy, orange-red hair and thickly exaggerated makeup. Looking like a 1940s thrift shop gone insane, she could be found wearing a turban, high platform shoes, a black-laced corset, gold lamé pants. She gyrated and gesticulated. Her substantial cleavage battled half-hearted attempts at restraint (“I’m D, the corset’s B”) and developed a stage presence of its own.

She unleashed a rich, booming voice on popular songs from the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. She tore into upbeat numbers like “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” oozed schmaltz into emotional standards such as “Friends” and in between numbers riddled the crowd with catty swipes and cheesy, off-color banter: “If Dick Nixon would only do to Pat what he’s done to the country ….”

The cartoonish excess was tempered by a sincere respect for the music and a need for acceptance that no amount of makeup could hide. This tacky, untamed powerhouse was downright accessible.

The crowd went wild. The scantily clad boys instantly knew they had found a kindred campy spirit. In this hidden world of the baths, Bette and the boys encouraged one another to let their guard down and do as they pleased. Through their shared wackiness, a strong affection developed between performer and audience.

Bette Midler was quickly joining the rank of female performers idolized by the gay community. Marlene Dietrich had aggressively blurred gender roles in the ’20s and ’30s, giving androgyny a famous face. Gypsy Rose Lee followed with unapologetic burlesque. Then came Judy Garland, most beloved of all, whose real-life struggles played out in constant contrast to Dorothy’s simple plea for the happiness that seemed to wait just over the rainbow.

Besides turning tradition on its head, these ladies shared a unique combination of no-holds-barred bravado and vulnerability that resonated with the gay community. Bette Midler fit the role like a glove.

She grabbed her diva status with force. First, she designated herself “The Divine Miss M.” Then she selected a backup group of three gum-chewing women outfitted in low-cut dresses and red platform shoes: “I guess you’re wondering, ‘Who are those three cocktail waitresses up there with Miss M anyway?’ They’re my girl singing group, the Harlettes …. They’re real sluts.” Rounding out the ensemble was a young pianist whose biggest claim to fame to that point was a McDonald’s jingle, a guy named Barry Manilow.

The buzz about The Divine Miss M quickly expanded beyond the walls of the Continental and won her frequent spots on Johnny Carson’s TV show. She would sit with Johnny when she finished singing and tell torrid tales of sweaty nights in a mysterious underground club.

Suddenly Bette and the boys were the talk of the town. Lines formed around the block. The previously marginal club was chic. Men in towels stared in disbelief as the likes of Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol piled into the place.

At the center was Bette Midler, hosting the bash of the early ’70s. The Woodstock lovefest was over, the Studio 54 revelry still years away. It was The Divine Miss M’s turn to throw a party, and she wasn’t done yet.