latimes.com Quantcast

http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/la-ca-retro26-2009jul26,0,1125766.story

From the Los Angeles Times

ON FILM

Retro, but still relevant

‘Wall Street,’ ‘Salvador‘ and ‘The Rose‘ — they’re all visions of the past, but they also illuminate the present. With movies in the summer doldrums, it’s time to revisit a few cinematic antecedents

By BETSY SHARKEY

Film Critic

July 26, 2009

I blame Bernie Madoff for this.

Or more precisely, it was a midnight collision of Madoff madness, insomnia and cable’s endless loop of films. Though if not for the saturation of news about the high-flying broker/con artist who trapezed across the financial markets to such devastating effect, I might have bypassed “Wall Street” in favor of something more mind-numbing.

But this 22-year-old cut at the risky business of stocks and bonds turned out to be unexpectedly mesmerizing. Instead of looking its age, “Wall Street” was crackling with the same electrical current that is shocking us today, which is no doubt why a sequel has been bandied about.

It was almost as if all those years ago, writer-director Oliver Stone and co-writer Stanley Weiser closed their eyes and envisioned the arrogance and audacity of a trader who could Ponzi away $65 billion in other people’s money and still sleep like a baby. Their canary in the coal mine was Gordon Gekko, played with a seductive soullessness by Michael Douglas. For Gekko, beating the street was a drug, greed was an addiction, ethics nothing more than a nuisance. It all felt so Madoff.

Which led me to wonder, what other cautionary tales would wear as well now? Films that circumstance has turned vintage chic; visions of the past echoing and illuminating the present.

Watching CNN and MSNBC, images from “Broadcast News,” “All the President’s Men” and “Network” began swirling. Footage of President Obama triggered less linear notions — “The American President,” “Do the Right Thing,” “Dave,” “Only Angels Have Wings,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” “The Natural” and on and on.

Yet there were a handful of events churning through the news that immediately conjured up what felt like direct cinematic antecedents, films so closely bound to situations in their sense and sensibility to be worthy of a second look.

And so, for your consideration, my “retro to relevance” list. It’s certainly not scientific, offered merely as a summer distraction for the movie-minded among you bored now that we’ve slipped into the season when theaters, like landfills, overflow with discards.

Hot stocks, cold hearts

Would things have turned out different if we’d paid closer attention to Stone’s portrayal of the financial market as a blood sport in “Wall Street”? Probably not, but filmmakers have been issuing warnings for years.

Consider the 1940 film “The Bank Dick,” with W.C. Fields wrapping razor sharp commentary inside a mumble and a whimsical box of nonsense. It’s the simple story of a bank, a bad stock deal that’s going even further south, some “early” movement of funds, and Fields, as the newly appointed bank detective, asking just about everyone he meets, “Not boondoggling, are you?” A 69-year-old question we might do well to pose to CEOs during their annual review.

Next up, 1990’s “Pretty Woman.” Don’t laugh. Julia Roberts’ hooker had solid negotiating skills and no credit card debt. The other significant love story was that of a family business trying to stay intact in the face of Richard Gere’s corporate raider. Watching his gamesmanship morph into decency as he discovers the virtue of building rather than fire sale-ing a business’ assets is a pure pleasure. And he gets the girl. For free.

For the final word, I’d turn to Woody Allen’s exquisite 1989 meditation on morality, “Crimes & Misdemeanors.” Yes, it was murder, not embezzlement, that Martin Landau’s Judah was rationalizing away, but witnessing his fear evolve into acceptance, then justification, then self-righteousness is terrifying. Sometimes it sounds like executives are cribbing from Allen’s script when explaining away their involvement in the latest corporate collapse.

Journalists without borders

On a wave of emotion and memory, 1982’s “The Year of Living Dangerously,” 1984’s “The Killing Fields” and 1986’s “Salvador” wash up. Different years, different wars, different countries, all capturing the high-stakes risk/reward of being a foreign correspondent.

It’s life balanced on a tight wire with no net, as we have been so painfully reminded with Current TV reporters Laura Ling and Euna Lee sentenced to 12 years of hard labor by the North Korean government, and the June escape of New York Times foreign correspondent David Rohde after more than seven months as a Taliban hostage.

In “The Year of Living Dangerously,” we watch as Indonesia’s unfolding chaos seasons a young Mel Gibson as reporter Guy Hamilton, the end coming with a bloody coup. Insanity and death clog the streets in the final scenes as Guy navigates absolute anarchy, the bit of paper that marks him a journalist all that can save him.

But emotion is forever shading the picture. For Gibson, it was his relationship with his Chinese photographer, an extraordinary performance by Linda Hunt. In “The Killing Fields,” the breaking heart of the film was the relationship between New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg and Dith Pran, the photographer he ultimately left behind in Pol Pot’s crazed Cambodia.

The human cost on both sides is set out in Oliver Stone’s “Salvador,” co-written with journalist Rick Boyle, on whose experiences the film was based. James Woods as Boyle is walking through a human dump, bodies rotting, vultures raiding. John Savage’s photographer, camera just inches from the dead, says: “You’ve got to get close to get the truth. . . get too close, you die.”

The dark side of fame

It has been impossible in the days since Michael Jackson‘s passing not to think of the long list of Hollywood deaths that linger in a fog of fame and drugs. The movies that start taking shape in my mind are “Frances” in 1982, “The Rose” in 1979 and 1972’s “Lady Sings the Blues.” (I’d include “The Doors,” but that would be casting one Stone too many.)

“Frances,” the story of actress Frances Farmer, explores the powerful and often destructive bond between stars and their stage parents. Played to utter devastation by Jessica Lange, the troubled star ends up in a psychiatric ward more than once at her mother’s behest; the sad theme that keeps repeating itself is not about getting her well, but back in the game.

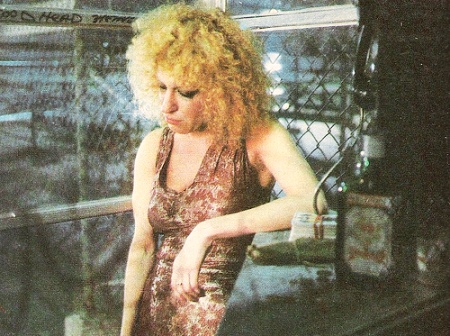

Though Farmer found a way to survive her demons, for so many others that is not how it ends. In “The Rose,” which starred Bette Midler as Mary Rose Foster, a barely masked Janis Joplin, and again in “Lady Sings the Blues,” the story of Billie Holiday starring Diana Ross, a death too soon is always the end game.

Tragedy is forever lurking in the shadows, just beyond the spotlight. You see it in “The Rose,” when the singer, exhausted from the road and the booze, begs for a year off, only to fold under pressure from a manager extremely facile at manipulating her fears; in “Lady Sings the Blues,” it’s the bandmate who begins slipping Holiday drugs to keep her going.

Like so many artists, Farmer, Holiday and Joplin came into fame already wounded. For a while, the adulation made the pain bearable, kept the insecurities at bay, but it never lasted long, and there was always someone nearby with something to take the edge off. And so they burned brightly, and then they died, too often confusing attention for love. You wish for a different ending.

When it all gets to be too much

As unemployment rates keep rising and corporate downsizing continues, I’d offer up “Lost in America” as a sort of coda to “Wall Street,” where this sleep-deprived excursion began. Albert Brooks’ 1985 treatise on dropping out captured disillusionment with the corporate rat race long before it would become epidemic.

As a rising ad man overlooked one too many times, Brooks quits his job and with his wife, Linda (Julie Hagerty), and a Winnebago, goes in search of a simpler life. What makes the film feel painfully modern is Brooks’ deconstruction of the meaning, usages and implications of having and losing one’s “nest egg.”

Which brings us back to Madoff, sentenced to 150 years for all the nest eggs he squandered. Maybe he’ll catch “Wall Street” on cable some sleepless night.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=49d51a45-ca9d-426a-930d-ae056435d2ca)