Mister D: I remember seeing Ms. Kael, who comes off harsh in this interview, being asked by late night broadcaster Tom Snyder whom she thought should win the Best Actress Oscar in 1979. She said, Tom there is no competition. The winner is Bette Midler. I haven’t seen an actress deliver lines like that in 30 years. If the Academy doesn’t give it to her then we know the whole organization is a sham. So needless to say, I loved the lady. But I never trusted the Oscars again lol  Most of the rest of what Ms. Kael is saying I truly believe she blames on the institution of Hollywood itself.

The Guardian

Kael: the last interview

Pauline Kael was America‘s most revered film critic. Shortly before her death last year Francis Davis spoke to her about Hitchcock, Jaws, the avant-garde and ‘terrible’ modern movies

Francis Davis

Thursday 31 October 2002

I assume that your Parkinson’s was the reason you retired from the New Yorker.

That, plus the fact that I suddenly couldn’t say anything about some of the movies. They were just so terrible, and I’d already written about so many terrible movies. I love writing about movies when I can discover something in them – when I can get something out of them that I can share with people. The week I quit, I hadn’t planned on it. But I wrote up a couple of movies, and I read what I’d written, and it was just incredibly depressing. I thought, I’ve got nothing to share from this.

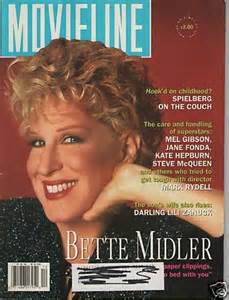

One of them was of that movie with Woody Allen and Bette Midler, Scenes From a Mall. I couldn’t write another bad review of Bette Midler. I thought she was so brilliant, and when I saw her in that terrible production of Gypsy on television, my heart sank. And I’d already panned her in Beaches. How can you go on panning people in picture after picture when you know they were great just a few years before? You have so much emotional investment in praising people that when you have to pan the same people a few years later, it tears your spirits apart.

Did you ever meet Alfred Hitchcock?

Yes. I was doing work for a radio show that was never completed, and I taped interviews with him and others. I didn’t have a very good time with him, because he wanted to talk about movies but couldn’t, because he hadn’t really gone to see anything. His wife had, and she was very knowledgeable and very pleasant. I liked her a lot, but he kept breaking off to talk about his wine cellar and his champagne collection. These seemed more vital to him than talking about movies.

I got very distressed when we talked about actors, because he had often cast people not after seeing them in pictures but from seeing them on a reel of film their agents brought, so that he saw only little highlights from some of their roles. He didn’t know the possibilities of some of the actors, and this was reinforced by his feeling that he shouldn’t improvise. Directors should not be allowed to improvise, he said, even though he had done a lot earlier in his career, and it was some of his best work. I think part of the rigidity of his later pictures was from his feeling that everything should be worked out in advance, which didn’t allow for any creative participation by the actors. You feel the absence of that participation in movies like Topaz and Marnie and, oh, I would say all of his later movies. He was quite rigid, almost like a religious fanatic.

Do you think this sometimes resulted in wooden performances, like Sean Connery‘s in Marnie?

Sean Connery I particularly asked about, because I was puzzled why he was so wooden in Marnie. Hitchcock said: “Well, that man never could act, you know, he could only play 007.” And I was astonished, because Connery was giving some of his greatest performances – oh, I shouldn’t say his greatest performances, because I think he became even better later, when he did The Man Who Would Be King, and some of his later films. But he was already doing marvellous work in that period, and Hitchcock didn’t seem interested in it at all – he didn’t seem interested in actors.

When you went to work for Paramount in 1979, at the urging of Warren Beatty, you helped to shepherd some movies into production, right?

Yeah, but I’d rather not talk about that, because in some cases the directors didn’t know I had a hand in getting their movies produced.

We were talking earlier about Jean-Luc Godard, whose early movies you championed.

I haven’t seen many of his more recent ones, because I haven’t been in New York for the past decade. I feel very cut off from what he’s doing anyway. I don’t feel drawn to it at all. I think that for a while he was perhaps the most important French director since [Jean] Renoir. He did absolutely stunning new work. He did what Altman was doing in this country – they were rather parallel in their thinking, in using the journalistic form and making films that were like essays. He was an amazing director, and maybe what he’s doing now is still amazing, but I haven’t seen the movies. I’ve seen a few, and didn’t feel the excitement I felt when I saw Band of Outsiders or La Chinoise or any one of a dozen of his earlier movies. There are amazing sequences in his Les Carabiniers. It’s not a very interesting movie, but sometimes we’ll settle for a brilliant image or sequence or performance. A lot of WC Fields comedies I love for a particular sequence; the rest of it doesn’t matter much.

You’ve often surprised interviewers by telling them that your favourite decade for movies was the 1970s. They expect you to say the 1930s or the 1940s, a period long enough ago to seem classic.

I love the fact that I wrote about movies in the 1970s, when there were directors coming along who really brought something new to the medium. Just think, I got to write about Godard and Truffaut, and Altman and Coppola, and movies that people don’t even talk about, like Hal Ashby‘s The Landlord, which was a wonderful movie from the 1970s.

Yet when you returned to the New Yorker in 1980, after your sojourn in Hollywood working for Beatty, your first piece was an essay called Why Are Movies So Bad? Or the Numbers. Did the stakes become too high to allow for the same sort of experimentation?

That’s exactly what happened. A few movies made inordinate amounts of money, and everything we hoped for from movies went kerplooie. A good movie brought in terrible consequences. Jaws is really a terrific movie. I laughed all the way through it. Yet it marked something. Then, with Star Wars coming on top of it, that awful Star Wars and its successors, movies have just never been the same.

There are hardly any small movies that people go to, and some of the more interesting ones they won’t go to. I loved Three Kings, which I thought was probably the best American movie I saw last year. But it didn’t have much of a following, even with George Clooney in the lead, and he was very good. Larry Kasdan’s Mumford, which was dismissed in the press, was a charming movie. But for some strange reason we don’t go to charming, light movies any more. People expect a movie to be heavy and turgid, like American Beauty.

Not being able to write about movies now must be frustrating; there’s a lot of damage that needs undoing.

I keep seeing movies I think are interesting that nobody is praising. Three Kings, in particular, got some good reviews, but nothing like it deserved. I thought Mission to Mars had some extraordinary sequences in it. I’m always attacked for liking Brian De Palma so much, and it’s a very uneven, erratic movie. But about half of it is superb, and I can’t understand why more people didn’t recognise that.

Let’s see, what else? Oh, I liked Flirting with Disaster, the movie that David O Russell made before Three Kings. I think it’s the best simple comedy from this country that I’ve seen in recent years. Lily Tomlin, Alan Alda, Mary Tyler Moore, and the other people in it are really very funny. There haven’t been many recent simple comedies like that; maybe we’ve gotten out of the habit of praising them.

I love movies that are more exploratory. I loved a French movie from a few years ago that very few people saw, a Bertrand Blier film called My Man, which got almost no press, but had something of the qualities of Last Tango. There aren’t very many movies that get at something new. There were scenes in The Conformist that movies hadn’t approached before, and Bertolucci did another good movie a couple of years ago called Besieged, starring Thandie Newton, who’s also in Mission Impossible 2. She’s extraordinarily sensitive and interesting, but the film never took off and the press didn’t talk about it very much. It’s very hard to get people to go see movies that aren’t as well publicised as The Perfect Storm or The Patriot. I can’t believe people I know go to see those movies. What do they get out of them?

Extracted from Afterglow: A Last Conversation with Pauline Kael by Francis Davis. © Francis Davis 2002. Reprinted by arrangement with Da Capo Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group. All rights reserved.

So Pauline Kael decided to retire cause she felt Bette was too brilhant for Hollywood? That sounds like a pretty good review too me.. :-p

Hollywood sucked so bad they couldn’t give her anything worthwhile lol

They really typecast Bette once all those comedies were so successful and no one was willing to give her anything really scenery chewing as she would say. I remember Mark Rydell saying he had a bunch of projects for her but no one was interested. Pauline was a great critic, was a great admirer of Streisand as well. She knew the goods when she saw it.

Yeah…It’s too bad nobody has any vision there.

The obvious disadvantage of this system for a daily newspaper is that by avoiding not only junkets, but free movie studio pre-release screenings, the review cannot appear on the morning the film opens in theaters. Pauline Kael was the most lauded film critic of her time.