Literary Hub

City of One Million Trees: How New York Inspired Other Cities to Go Green

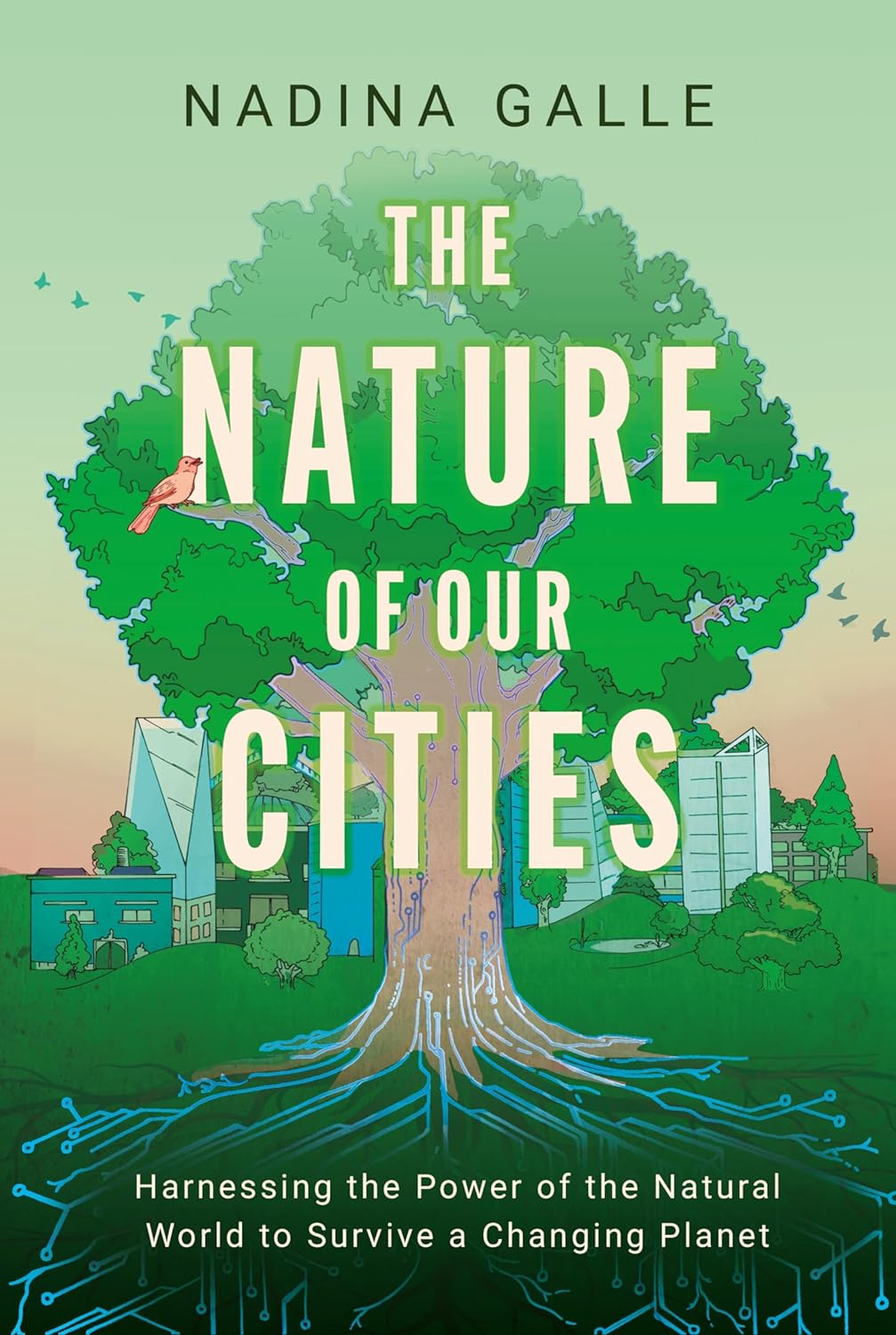

By Nadina Galle

June 21, 2024

Singapore is one of the world’s greenest cities. With seven million trees and one million more expected to be planted by 2030, Singapore’s inventory is a “digital twin”—developed by capturing measurements using light from a laser directed around each block and then applying artificial intelligence to geolocate each plant. Arborists at Singapore’s National Parks Board (NParks) can track their trees through an app and conduct several digital inspections, like examining overall tree stability under fierce tropical storms. It has a network of physical tilt sensors, which measure sudden movement and indicate risk, remote sensing to determine healthy chlorophyll levels, and street-level cameras for remote visual checks—all of which play a role.

In 2000, N Parks reported about 3,100 “tree incidents”—where a branch falls, or a tree trunk snaps or is uprooted. Most notable in the years since was a 270-year-old tembusu tree, which fell during a concert in the Singapore Botanic Gardens, crushing a family. Concertgoers rushed to lift the massive tree—saving the father and one-year-old twins, who suffered injuries. But it was too late for the children’s thirty-eight-year-old mother, who was killed. The tragedy showed the community needed a better way to manage its forest.

Over the next years, the city focused on continuously improving its tree database and tree care, eventually leading to the inventory model and its companion app. By 2020, NParks reported a nearly 90 percent decrease in annual tree incidents. By identifying potential safety hazards and assessing each tree’s overall health and maintenance needs, NParks proved it could address issues before they became dangerous to people and property. It restored confidence in the safety of its trees that the Botanic Gardens incident had shaken, building public support for growing the urban forest after years in which some residents had begun to question the value of trees. In doing so, it provided a model for cities worldwide, which struggle to field all the complaints from residents worried that an unkempt tree might harm them or their homes.

The movement that Singapore championed to value and manage the urban canopy properly had begun years before in New York City. The most densely populated city in the United States, its soil stuffed with thousands of cubic feet of “utility spaghetti,” New York started its tree census practice in the 1990s. Still, the project had taken on much greater significance after the city began to appreciate its remarkable forest anew following the World Trade Center attacks.

The story started a few years before that, with a public effort to count every tree across the city. The city’s parks commissioner had delegated the action to Fiona Watt, a recent forestry graduate who had only started working for the parks department five days before. Though she felt completely unprepared to lead what may have been the world’s first urban tree census in a major city, Fiona wanted more than anything to prove that it was possible.

Years before digital mapping systems and sensors could automate the process, Fiona knew she would need an army to canvass the city. So she and the longtime parks commissioner, Henry J. Stern, invited the public to help. Commissioner Stern asked anyone willing to help count trees at the press conference to call a new hotline: 1-800-360-TREE.

When people called, Fiona was on the other end of the line, madly scribbling down their names and phone numbers. Within days, she’d amassed an infantry of two hundred volunteers. It launched a new era for NYC Parks, in which citizens were grossly more engaged in the trees they shared their streets with.

Fiona used her forestry background to determine the variables to measure in the field. It started simply with the location, species, size, and condition. Everything was done by hand. Without the online maps we rely on today, Fiona had to use road atlases, which she annotated for her new community workers, laminating the paper to protect it from the elements. Each volunteer received a map highlighting the polygon they were partly responsible for and a stack of data-collection sheets on a clipboard. Later, the city contracted a company to keypunch all recorded information into a rudimentary database. It was the first technological leap for the newly dubbed “TreesCount!” campaign.

The first tree census revealed surprising truths. For starters, 10,000 dead or dying trees had gone unnoticed. The observation sparked new programs devoted to pruning trees and replacing the dead with stronger saplings. Perhaps even more surprising, the census helped to explain why so many New Yorkers felt deeply connected to the urban forest: it was far more widespread than anyone realized. In a city better known for its glass and steel towers, trees outnumbered the skyscrapers more than 500 to 1.

In the weeks following the September 11 terrorist attacks, the importance of New York City’s parks only became clearer. With the city mourning the 2,753 fallen, parks emerged as a place of healing. In a letter to the public just two weeks after the attacks, Commissioner Stern wrote about people lighting candles, writing messages, leaving flowers and flags, and consoling one another in their neighborhood parks. “Our city has sustained a tremendous loss,” he said, “but with your help, parks can play an important role in the psychological recovery.”

Fear, economic downturn, and respiratory conditions linked to exposure to the World Trade Center collapse—which would eventually claim thousands more lives—had residents fleeing the city. When Michael Bloomberg became mayor three months later, smoke was still rising from downtown. Many people wondered whether Lower Manhattan would ever come back.

But as residents continued to filter out and the city mourned, its trees continued to purify the air. Some reminded the public of the resilience we all share within us. When the World Trade Center site was developed as a memorial park where those who had lost loved ones could reflect on the tragedy, its designers transplanted a Callery pear tree at its center. The tree had been discovered among the rubble, nearly incinerated but still showing signs of life. Workers nursed it back to health for a decade, sprouting new branches and flowering in spring; it grew from eight to over thirty feet tall. With limbs extending from gnarled stumps, the “Survivor Tree” experienced what so many New Yorkers did that day. Badly burned in the rubble, it remarkably recovered, sprouting new growth the next season. As one survivor of the attacks reflected, “[it] reminds us all of the capacity of the human spirit to persevere.”

When Fiona returned from her third maternity leave to tackle the city’s next tree census in 2005, it was clear the stakes had grown. Her colleagues at the Forest Service’s New York City Field Station had begun to document how New Yorkers created “living memorials” or green spaces dedicated to memorializing those lost in the 9/11 attacks. Her neighbors across the city were more tuned into their reliance on nature than ever, with new organizations devoted to nature popping up yearly.

So she tapped into that enthusiasm, using promotional campaigns to help quintuple the tree-counting infantry. This time, she also hoped that better technology could make the volunteers more efficient. Instead of just pen and paper, she distributed handhelds with a rudimentary web app to her more than one thousand volunteers, who could now immediately input data into the system. At the end of 2006, volunteers surveyed over 590,000 street trees in excruciating detail. Next, Fiona called for the help of the one person she knew could motivate the city to use this data revolution.

Dr. Greg McPherson, Fiona’s one-time professor, was a uniquely urban-focused researcher with the U.S. Forest Service. Calling himself a “green accountant,” he researched new methods and tools for quantifying the value of nature’s benefits from city trees. He created a model for leaders to battle for the budget to maintain their trees and expand urban forests. Dr. McPherson called the model the Street Tree Resource Assessment Tool for Urban Forest Managers (STRATUM), which was later adapted to a state-of-the-art, peer-reviewed software suite called i-Tree Streets and, more recently, i-Tree Eco. To this day, Dr. McPherson’s model remains the gold standard for thousands of communities, nonprofits, consultants, volunteers, and students worldwide to calculate the benefits of trees.

The model hadn’t yet launched when Fiona called him. But having heard about it, Fiona knew it could give her exactly the data that New York needed for city leaders to understand the role of trees in people’s lives. Dr. McPherson told her it wasn’t ready. It was early days, and he hadn’t completed the reference studies for New York—or any East Coast cities, for that matter. Since the model was based on West Coast tree species, growth patterns, and climate conditions, it would be useless, he said.

Not one to take no for an answer, Fiona secured a grant from the state to adapt and apply the model to New York City. With Dr. McPherson’s engineering, it worked. Within a few months, Fiona got the results that would forever change the face of the city’s forest: for every dollar spent on tree planting and care, trees provide $5.60 in benefits, capturing carbon dioxide in their tissue, reducing energy used by buildings, decreasing air pollutants that can trigger asthma and other respiratory illnesses, and acting as natural stormwater retention devices, with the combination of these benefits increasing property values. For the first time, the NYC Parks Department could translate the value of the city’s trees into dollars and cents.

Fiona immediately took the results to her boss, Adrian Benepe, the parks commissioner who followed Stern, who then presented it to Mayor Bloomberg. As a former investment banker turned entrepreneur, the mayor had stacked his administration with ex-executives and bankers, people who appreciated return on investment (ROI) like no other administration before. As Adrian presented the data, all the administration heard was a 560 percent ROI. It paved the way for the biggest investment in street trees the city had ever seen.

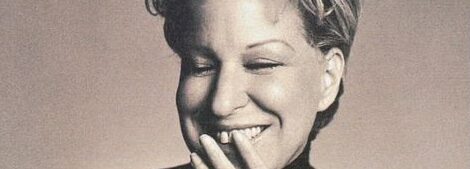

It took the form of a collaboration with Bette Midler, who’d recently founded a nonprofit dedicated to cleaning and restoring green spaces in the five boroughs called the New York Restoration Project. Inspired by tree-planting campaigns she’d seen in other cities—from Los Angeles to Denver to Boston—Bette, who had moved to New York City, felt the city needed to do something even more ambitious. While walking in the park with the mayor, for whom the ROI data was undoubtedly top of mind, she told him about her vision for her organization. Together, they conceived the MillionTreesNYC initiative.

Fiona told me about the program while we stood in the shadow of a thirty-some-foot-tall Carolina silverbell in the Morrisania neighborhood in the South Bronx. It was a warm September morning, and we stared up at a cardinal gliding down to a nest of squawking chicks. Bette had picked this location for the first tree that the initiative planted. One of the areas with the city’s highest asthma rates, the intersection at East 166th Street and Washington Avenue was otherwise starved of vegetation. The MillionTreesNYC initiative was supposed to take ten years, but fueled by a new purpose among city workers and tens of thousands of volunteers, it finished two years ahead of schedule. Not even two fierce storms, Tropical Storm Irene and then Hurricane Sandy, which created months of cleanup work for tree crews, could slow the momentum of MillionTreesNYC.

Most importantly, after years of disinvestment in less affluent areas, the initiative helped to restore equal access to trees. Of the million new trees, the Bronx received 280,000; Brooklyn, 185,000; Manhattan, 75,000; Queens, 285,000; and Staten Island, 175,000.

By 2015, when Fiona oversaw the third iteration of the TreesCount! campaign, the initiative’s success was readily apparent. Notwithstanding the effects of Hurricane Sandy three years prior—the most devastating weather event in the city’s recorded history—tree numbers had surged 12.5 percent from 2005 and 33.6 percent from 1995.

Fiona had been able to measure this success in part because she continued to innovate the census. In 2015, she implemented geographic information systems (GIS), a mapping technology specialized for storing metadata such as tree size and shape. With GIS, the census could collect nuanced data showing the campaign’s massive investment benefits.

As Jackie Lu, the inaugural director of data analytics at NYC Parks at the time, explained, each census needed to build from the last. The first supported implementing a block-by-block tree maintenance program, allowing the city to prune trees on rotation for the first time and intervening before dead branches became dangerous. The second census enabled the calculation of the ROI of the city’s street trees, making the business case that launched MillionTreesNYC. It forced city leaders to take the Parks Department seriously for the first time.

The third census, by contrast, was a test case, evaluating if the benefits of new trees promised by the 2005 census could be realized. At the heart of the latest initiative was a new technological leap—a tablet-and smartphone-based tallying system that would make the job of “volun-treers” faster, less labor-intensive, and more accurate. In the past two censuses, the mapping was based on addresses, and as a result, the locations where canvassers pegged trees were often imprecise. Since nearby trees can often look alike, the data confused the foresters who would later use it.

Jackie and Fiona’s challenge was designing a recording method simple enough for nontechnical volunteers yet accurate enough that foresters could finally trust it. A local nonprofit called TreeKIT stepped in to help. It designed an app combining century-old technology—a measurement wheel similar to land surveyors pushing around on an axle—with modern-day GPS capability. Using the GPS’s orientation and human measurements, the wheels could record each tree’s location relative to the surrounding intersections and buildings. Jackie’s quality control confirmed that volunteers with the device mapped trees almost as accurately as her staff.

Soon, NYC Parks became the nation’s largest purchaser of surveyors’ wheels. The effort took two years to complete.

Even then, it wasn’t done in Jackie’s eyes. To keep volunteers engaged for years to come, she wanted to ensure she let them in on exactly how—and why—the data they were collecting was used. So, after operationalizing the data and bringing it into the software NYC Parks uses to manage the urban forest daily, she made a public-facing version. The NYC Street Tree Map is now the model for cities with similar ambitions. Continuously updated by the foresters who use the backend, it offers an interactive tool designed to be a central hub for everyone interested in their neighborhood trees. You can identify the ecological benefits of your street tree, contribute data, track the tree’s care, organize your tree care group, and—of course—submit service requests to the city.

As Fiona and I leave the shade of the Carolina silverbell that started it all, we wade through a sea of cars waiting at a stoplight and further into the Morrisania neighborhood. I immediately feel the sun’s heat, a pulse on my forehead. Fiona glances back when she makes it to the sidewalk as if to make sure I’m still there, and she squints to see me through the glare. Her dirty-blond hair is pulled back in a tight ponytail, a few abandoned pieces hanging down her cheeks.

We both turn around to face the tree, following the line of the thin trunk reaching toward the top of the brownstones. Taking in the sight of this oasis in a busy intersection, I wonder whether other cities could replicate the success of the TreesCount! campaigns. For the first time, there is finally money to do so. As of August 2022, the U.S. federal government is making a whopping $360 billion investment to address climate change. Forestry projects have been allocated a $5 billion slice of the pie, with $1.5 billion set aside for the U.S. Forest Service Urban and Community Forestry program, which distributes funding to local governments and community organizations. To capture this funding, cities need accurate tree inventories, so they are motivated to get their hands on accurate, cost-efficient data. But will they have the community engagement and department-led expertise to build a database from scratch—and more quickly than New York City ever did? After all, with funding starting to be distributed, they don’t have the years that each TreesCount! the census did catch up.

“So what’s next for the 2025 census,” I ask, trying to distract myself from the hopelessness I can feel. She tells me she’s excited for a new technology she heard about at a recent conference. “LiDAR,” she says, “but, you know, on the ground.”

She looks at me for help.

“Terrestrial LiDAR?” I offer.

“Yes, that’s it. I’ve heard cool things. It could help cities get incredibly granular tree inventories more quickly.” She was describing the technology that would eventually facilitate Singapore’s campaign.