San Fran Chronicle

Looking at how film comedy lasts – or doesn’t

Mick LaSalle, Chronicle Movie Critic

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Funny thing about comedy. It’s the truest and most enduring genre, universal and timeless in its appeal. But it’s also the genre with the worst shelf life, that dates poorly, that can go from delightful to pointless within a generation, sometimes within a decade.

Watch Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Groucho Marx or Jackie Gleason, and the years fall away. Yet just try to sit through a Martin and Lewis movie – it’s excruciating. Even weirder is watching things that you once thought funny, say Frank Gorshin’s impressions or Freddie Prinze’s stand-up routine. The audience is laughing, and they seem to mean it, and yet what’s so funny about Prinze calling himself a “Hungarican,” just because his mother was Hungarian and his father Puerto Rican?

Looking over the movies of the past few decades, we can already see what’s going to last and what’s going to be forgotten. Woody Allen is still funny, even his earliest movie as a writer-director, “Take the Money and Run” (1969). In fact, once you get to “Annie Hall” (1977) and “Manhattan” (1979), Allen’s movies don’t feel as though they’ve dated at all. To a lesser degree, neither does the best of Mel Brooks’ work. By contrast, Chevy Chase’s movies from around those same years play like something uncovered in an archaeological dig.

In the case of Chase, he was a funny guy, but his movies weren’t. That was a familiar pattern a generation ago: Imagine if you only knew John Belushi, Richard Pryor and Rodney Dangerfield from their movies? Pryor’s concert films will always have their place, and some of Steve Martin’s early films may retain interest, if only for what they indicate of Martin’s later work. But is anybody really going to be watching “Animal House” or “Ghostbusters” in 2050? I doubt it.

Comedians have their moment, seem invincible … and then the power ebbs away. Eddie Murphy was one of the biggest stars of the 1980s, and then some time around “Harlem Nights” (1989), the graph started pointing downward. Jim Carrey was huge in the 1990s, but the formula began to go stale with “Bruce Almighty” (2003). The public discovers someone, sees him or her (usually him) as the embodiment of some previously unknown truth about people or human nature. And then eventually that interest is satiated, and the comedian must either fade or innovate.

In the 1990s, Adam Sandler was one of the exemplars of the Disturbed Idiot genre – a popular comedy subtype that also included Carrey, Pauly Shore and Tom Green. But since then, Sandler has branched out into semi-dramatic roles, including this summer’s “Funny People,” while Carrey hasn’t quite found his next move. Shore and Green have faded to the margins.

Eventually, everyone falls out of fashion. Chaplin lost his popularity in the late 1940s, and Keaton was considered a has-been long before he turned 40. Keaton had to be completely rediscovered in the ’50s and ’60s, while Chaplin had to be, at the very least, reappreciated in the 1970s. But when fans and scholars went back and saw the work, there was great comedy there to see. The jokes held up.

Right now, Murphy and Robin Williams are somewhat out of fashion. But I think Murphy’s concert movies, “Delirious” and “Raw,” will stand the test of time, and so will “48 Hrs.” and “The Nutty Professor.” As for Williams, he has definitely done work that will last, though I suspect he might very well be best appreciated as an actor with a funny streak, rather than as a straight-up comedian.

I could have mentioned “Beverly Hills Cop” among the Murphy movies, but I chose not to because he’s cool in that movie. And coolness is so tied up with an era’s misconceptions and fleeting assumptions that it puts a sell-by date on comedy, which curdles in the absence of lasting truths.

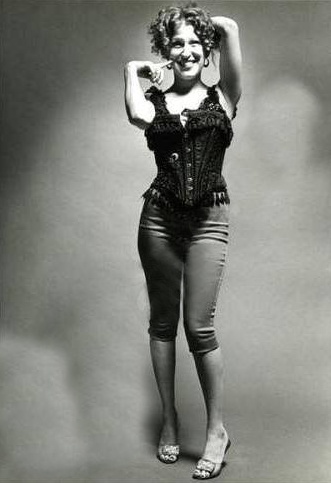

Among the women, something honest and perceptive – some timeless understanding of human nature – is present in the work of Lily Tomlin, Bette Midler and Goldie Hawn. They have their place in the Funny Lady pantheon (ruled to this day, by Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard and Lucille Ball). Speaking of “Funny Lady,” is there anything less funny than a Barbra Streisand movie from the 1970s?

Of the screen comedians dominating movies today, four stand out: Will Ferrell, Ben Stiller, Steve Carell and Seth Rogen. Ferrell is the most naturally funny, but he has to guard against vanity, which was Murphy’s problem in his heyday.

Carell and Stiller are both good comic actors. Their challenge is to find material worthy of them and not succumb to the lure of ephemeral fluff, such as “Get Smart” (Carell) and “Night at the Museum” (Stiller).

In a way, Rogen is the most exciting of all of them, because despite being very young – 26 – he has not let fame go to his head. So far. His work is versatile, honest, without vanity and very funny. He just might have it within him to be great, but getting there won’t be easy.

More than anything, doing lasting work as a screen comedian requires an invincible vision of oneself and the world. It’s a kind of confidence that, from the outside, might easily be mistaken for insecurity – a self-understanding and skepticism utterly impervious to success or praise.

The other day I was flicking around the dial and watched 20 minutes of Bill Murray in “Stripes” (1981). It was so clear: Whatever misconceptions people were walking around with 28 years ago, Murray was immune to them. Whatever vain assumptions were in the air, Murray wasn’t buying them. Everything he did in that film was true to who that guy was. There were silly jokes, but no cheap jokes. The guy would not lie.

And he hasn’t lied since.

That’s how you do work that lasts. That’s how you become a great comedian.