Toronto Star arts editor Archie Williamson, 60, dies

Crafted, edited entertainment pages with unusual flare

There was a moment last July when the people gathered upstairs at Bistro 990 for Archie Williamson’s surprise 60th birthday party began to think they’d be happier elsewhere.

It was the moment the guest of honour arrived.

His red hair bristled, his back stiffened – Mr. Williamson wasn’t a tall man but he had an alarming ability to loom – and his eyes flashed fire. He looked like an angry Scots terrier. And then his taut face collapsed into a happy smile and he said later it was one of the best evenings he’d spent. That was after he’d asked if he was going to have to pay for it.

Mr. Williamson enjoyed playing the gruff, irascible Scotsman. But it was a pose. Look carefully and you’d usually spot a twinkle in his eye. That’s unless he took you for a fool. He didn’t suffer fools at all, let alone gladly.

The night entertainment editor at the Toronto Star since 1969, Mr. Williamson died yesterday at 10:30 a.m. at Toronto Grace Hospital after fighting prostate cancer with characteristic, uncomplaining grit. When doctors told him last year his condition was terminal, he went around the newsroom and quietly broke the news to a few, special friends. He made it clear he didn’t want sympathy from them.

Photographer Tony Bock recalled a conversation the two had 10 years ago. “He told me he was the first male in his family to survive to 50. They weren’t a long-lived family.”

Managing editor Mary Deanne Shears called Mr. Williamson “a master of creativity … the best-dressed male journalist I’ve ever worked with. His silk bow ties were gorgeous and so was he.

“Archie just loved entertainers and the journalists who covered the arts and entertainment business. But, of course, he would never admit that. And he loved this newspaper, too, and was one of its frequent critics. He regularly made sure that I and everyone else knew when we did well on a story and when we didn’t.

“I shall miss him very much.”

Mr. Williamson worked with 14 entertainment editors, including Canadian icon Peter Gzowski, and took no nonsense from any of them. He used to say, only half jokingly, that he wanted to paint their heads on his computer, the way a fighter ace might mark his “kills” on his plane.

Sunday editor Lesley Ciarula Taylor recalled butting heads with him one evening not long after she’d become deputy entertainment editor.

“Archie came at me in a fury about something,” she said. “I backed down and then he came back later to tell me I wasn’t doing my job if I let him get away with a tantrum like that. I was new and he was training me, the way he trained us all.”

Mr. Williamson’s job title changed over the years but the work remained the same: Designing and editing the nightly arts and entertainment pages under pressure of deadline for 34 remarkable years.

There was no question about who was in command once he was at his desk. He would wait for the entertainment editor to leave the building before laying out the pages his way, pausing only for his nightly ritual meal of melba toast, carrots and an apple.

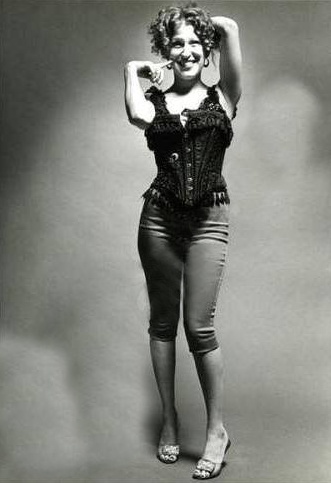

He even left strict instructions about what photos to use with this obituary.

“Archie is still dictating layout,” movie critic Peter Howell noted. “He’d get a laugh out of that.”

Mr. Williamson would proudly claim that he never once had a critic freeze on him and be unable to write a review on deadline. No one would have dared. Reviewers would rush in from a play or concert and be told how many inches they had to fill and how long they had to fill them. There was no negotiation.

He was punctilious in every aspect of his life. You could set your watch by his arrival in the newsroom – 4:53 p.m. every day. In the summer he’d sometimes be wearing a pith helmet. He admired Germans for their punctuality and was pleased that every day when he waited at the light at Lakeshore Dr. and Yonge St. that the flight attendants on the Lufthansa shuttle bus would greet him with a wave.

Mr. Williamson’s three passions were chocolate, his beloved Volkswagen and Mexico. He would drive there – alone; his partner Barry Bandurk preferred to fly – every summer.

“It was all the more remarkable because Archie was fair skinned and hated the sun,” said Stargazing columnist Rita Zekas. “He learned Spanish so that he would thwart the bandidos along the way. He made a point of driving a car with dark tinted windows and when he was stopped, there would be this gringo with pale skin and violently red hair, spouting fluent Spanish. He claimed they thought he was CIA.”

His trip schedule was so nitpickingly planned, he even listed his rest stops and what time he’d arrive at them and leave.

None of his fellow workers could visit any of the chocolate-producing countries in Europe without bringing him back a sample.

Mr. Williamson was always ready to tear apart a page to get entertainment obits in the paper.

“What if Bob Hope dies?” was his standard response when presented with a pre-designed page.

More than one co-worker remarked yesterday that he would be chagrined that Hope outlived him, denying him the opportunity to write a “thanks for the memories” headline.

“Ironically,” said jazz critic Geoff Chapman, “Archie was brilliant at making over pages for the death of big entertainment stars. Archie was a star, too.

“As an editor he was a dream to work with. He had the knack of working with several writers at the same time. He was quick to respond and very knowledgeable, as likely to discuss the merits of Mahler as the acting subtleties of Betty Grable.”

Items about his favourite stars, such as Elizabeth Taylor, Bette Midler and Liza Minnelli, invariably found their way into the paper. And he would make sure they were smoking in the photos.

“If he didn’t like the stars,” pointed out Zekas, “he would be sure to pick out photos that made them look fat and/or old.

“Archie had a gruff exterior but inside was a ball of mush. Freelancers didn’t know that. One high-powered woman used to do freelance classical music reviews and she was so terrified of Archie, she would write them in the women’s washroom.”

As a proud but understated gay man, part of Mr. Williamson’s legacy, colleagues say, was his quiet role in making the entertainment section a gay-positive media voice long before it became fashionable. Although the fact that Elizabeth Taylor’s photo has appeared 79 times and Bette Midler’s 75 times since 1985 was the most obvious manifestation, he had much more subtle influences on expanding tolerance and broad-mindedness in editors, writers and readers.

He was proud of the fact that he’d not only met Liberace, the flamboyant pianist always sent him a Christmas card, which he carefully filed with the ones from years gone by.

During his career Mr. Williamson handled the copy of some of the country’s outstanding critics, including theatre critics Nathan Cohen and Urjo Kareda and film critic Clyde Gilmour.

His favourite was Kareda, “the best theatre critic I ever worked with.”

Mr. Williamson knew a pro when he saw one for the very good reason that he was one himself. If he thought you were talented, he encouraged you. If he found you wanting, you’d best look for a job in another part of the paper.

“Archie was the rock, the consummate professional,” said city editor John Ferri, a former entertainment editor. “His brilliance was in making the job look easy. He cared about the quality of the journalism as deeply as anyone I’ve ever met but it wasn’t something he’d admit in public. He let the work speak for itself.”

Mr. Williamson was born in Glasgow, a place of which he had few fond memories. A typical Scotsman in some respects – he viewed the English with a jaundiced eye – he broke the mould in other ways. He loathed the skirl of the bagpipes, shortbread and Scotch, for example.

He worked for the tabloid Scottish Daily Record and Sunday Mail from 1958 to 1965 before emigrating to Canada and joining the Star as a copy editor on Oct. 4, 1965.

One of his 14 entertainment editors was Alan Marshall, now an assistant managing editor, who also worked on the Record.

“I missed working with Archie by four years in Scotland,” Marshall recalled. “But he thought of me as a former colleague – and loved to point out what the Record head would have been on a particular Toronto Star story. He was that extraordinarily rare being: A great journalist who could do the job and still stay a wonderful, loving human being.”

“He is the conscience of the Entertainment department … its steadiest driver,” said then entertainment editor Sid Adilman in 1990, when Mr. Williamson completed 25 years at the Star. “He is the magician who makes up and makes over the pages Monday to Friday, always making them look lively, rarely cluttered and always with an eye to what the average reader wants.”

“It was clear to me from the moment I arrived that Archie was the soul of the section,” said Peter Scowen, who became Arts and Entertainment editor last August. “Everyone knew everything would be all right as of 5 p.m., when he came and sat down at his desk. Everyone happily deferred to the gruff Scotsman.

“He was a tremendously brave and stubborn man who came to work in spite of the awful pain he was often in. I think he did it because he loved the paper and he loved the people he worked with.”

Joe Fox, who worked closely with Mr. Williamson for the past 15 years, recalled his “stoicism amidst the clash of egos, stress of too many stories for available space and the pressure of meeting two or more deadlines a night for more than 30 years. He taught a string of copy editors who worked under him valuable lessons.”

Of Mr. Williamson’s often-hidden softer side, Kathy Muldoon, who also worked with him for several years, recalled: “Archie was the first person through my door when I came home from the hospital after having my daughter 15 years ago. There was no keeping him out. He loved babies and couldn’t wait to hold one.

“He requested a cup of tea and hefted this squalling infant to his shoulder, and walked around with her quietly for hours. I remember being worried about what would become of his freshly starched and ironed white shirt, always with the cuffs turned back twice.”

Vian Ewart, another former entertainment editor, called Mr. Williamson “one of those hardy Scots who could weather any storm, survive any turmoil. You could almost see him grit his teeth, shake his head of red hair and battle through the crisis of the moment. And he always won.

“During the two world wars, when the fighting reached its toughest, the British army always used to call up a certain regiment of Scottish troops to do their dirty work. Archie would have been one of those soldiers.

“If he let you on his side, you were there forever.”

Mr Williamson is survived by his partner, Barry Bandurk, his sister Elma Kennedy and her husband, Robert; his nieces Lorna and Gail and his nephew, Fraser; and his wheaten terrier, Erin Brockobitch. There is no funeral – but there will be a wake at Bistro 990. In lieu of flowers, please make donations to Toronto Grace Hospital palliative care unit.