Newsday

THE BUCK STARTS HERE

Clear Channel money pie made with celebrities

BY WARREN BERRY. STAFF WRITER

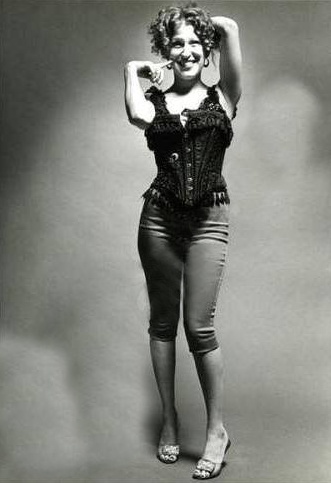

Who needs Howard Stern flapping his mouth when you can

make just as much money baring Britney Spears’ navel or Bette Midler’s tonsils

or Donald Trump’s brainstorms?

If you broke down the business plan at Clear Channel Communications (CCU),

those are the kinds of faces you’d see on the pie chart.

It must be comforting to be a communications company so well-off that you

don’t break a sweat as you order your radio stations to drop morning drive

time’s No. 1 “shock jock.”

It’s quite a contrast with other companies such as Martha Stewart Omnimedia

(MSO) or even Warren Buffett’s Berkshire-Hathaway (BRK), where a single person conceivably could determine an entire company’s future. At Clear Channel, when things get dicey with one prima donna, there’s always an 8-by-10 glossy of another potential moneymaker on the corkboard.

Clear Channel may be best- and most-controversially known for being the

nation’s dominant radio company, but it also happens to be one of the world’s

largest promoters of live entertainment and is the owner-operator of more

concert venues than practically anyone around the globe.

Fresh from triumphs with Britney and Bette, it trots out an ageless Madonna

and such perennials as David Bowie and KISS, heavy metalers who have just a

coating of rust. On radio, some critics contend, the programming is too

predictable, yet the national offerings do run the gamut from the Rev. Jesse

Jackson to The Donald, who during the next season of “The Apprentice” will tell

us all the next day why he canned contestants. (This could be one of the few

times when a radio show was inspired by TV rather than the other way around.)

Last week the company revealed a 64 percent surge in first-quarter earnings

to $116.5 million, aided by the $47-million sale of its stake in Univision

(UNV), the Latin-American network. But even as it predicted further

“double-digit” gains for the full year, the company said longtime CEO Lowry

Mays had undergone brain surgery April 30 after feeling numbness on his left

side. By Thursday, though, his son Mark Mays, Clear Channel’s president and

chief operating officer, reported that “the surgery was successful and Lowry is

in good spirits and mentally alert.” Lowry Mays is the driving force in the

expansion of Clear Channel, which acquired nearly 1,200 stations after the

Telecommunications Act of 1996 ended the 40-station ownership cap. (It isn’t

going unchallenged. In August, a lawsuit by a rival Denver promoter is to go to

trial, charging that Clear Channel used its dominance to block publicity of

competitors’ events.) The stock is at around $41 a share, midway between its

high and low for the past 52 weeks.

The company reported that a slight improvement in advertising boosted the

radio division’s revenues 5 percent to $833 million. But thanks to the likes of

Bette and Britney the entertainment division’s sales jumped 17 percent to $514

million.

There’s a less-glamorous side to Clear Channel: Outdoor advertising, not as

venerated as show biz, where revenues jumped 16 percent to $522 million. But

this is no longer a business built around those big billboards that community

beautifiers love to hate. “Outdoor” encompasses all kinds of nontraditional

media such as electronic messaging boards and paging systems at airports. And

there’s “street furniture,” which can encompass anything from a public bench

(with advertising message of course) to a bus-stop shelter. In Pittsburgh,

Clear Channel developed an offshoot: The stand-alone public toilet. It’s

something every city might go for some day, a secure little one-room house with

coin-operated entrance, good lighting, tasteful design and its own

self-cleaning floor.

Who needs Howard Stern?