People Magazine

January 07, 1980 Vol. 13 No. 1

The Divine Miss M

By Peter Lester

After Capturing Janis and Being Compared to Barbra, Nothing’s Too Lofty for Bette Midler

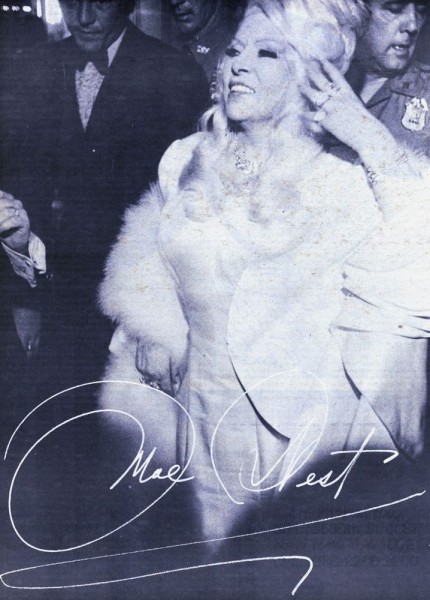

She combines into one provocative 5’1″ package the raucousness of Lucille Ball, the angst of Lily Tomlin and the randiness of Mae West. But having turned vulgarity and outrage into an art form, the remaining question is whether Bette Midler is to become a Streisand-level superstar of the ’80s.

Certainly, at 34, Bette has made her run for it, daring in her first starring Hollywood role to play a Janis Joplinesque chanteuse in The Rose. Ol’ Red Hair went “Venetian blond” as a self-destructive singer who OD’s on drugs, sex and rock’n’roll. Proclaimed Rex Reed, for one: “Streisand seems like a has-been.” Midler, for whom nothing is sacred, is nonetheless appalled by such invidious comparison: “It’s like taking a snipe at the Statue of Liberty, like a gnat chewing on the heels of an elephant.” Yet Bette is almost assured an Oscar nomination for The Rose, and she could match Barbra in capturing the grand slam: Tony, Grammy, Emmy and Oscar. Indeed, even Midler is heard crowing these nights in her Broadway showcase (Bette! Divine Madness): “Give me some respect! I’m a screen goddess now!”

Midler chose The Rose with great care. An extra in the films Goodbye, Columbus and Hawaii, she claims to have turned down Goldie Hawn’s role in Foul Play, Talia Shire’s in Rocky, Stockard Channing’s in The Fortune and Barbara Harris’ in Nashville. That her emotionally flat-out performance in Rose ultimately proved so powerful derives from the titillating idea that she was in part playing herself. A Joplin admirer long before she went into the part, Midler nonetheless vowed, “This isn’t going to be Janis, this is going to be me and whomever God can conjure up.” Like the movie’s Rose, Midler says she was herself once a “vicious drunk” who staggered from grasshoppers to stingers to brandy and has now all but quit–”only,” she notes, “because I lost so many friends, people I loved.” Bette, too, suffered the terror of performing. “When I could do a show without throwing up in the intermission, it was a terrific breakthrough. It got to the point where every show was a comeback for me.”

The Joplin parallels even include the movie scene when a sweating, gasping Rose runs offstage to her dressing room and immediately begins to make love to her man. “Oh, yeah,” Midler concedes, “I’ve made love before going on the stage too. Well, you do get hot. The crowd is so exciting, how can you help it?” A tougher scene for the enthusiastically heterosexual Midler was to create Rose’s lesbian affair. “That was a nightmare. I’m real straight, but we were really trying to be sympathetic. I jumped into it, hugging and kissing this girl,” she recounts. “When my manager, Aaron Russo, saw the dailies, he about jumped out of his drawers. He said, ‘How could you do that? I told you. No tongue!’ I thought it was nice, though they cut it all out in the film.”

Until last year, of course, Russo was the real problem Midler shared with the Rose character: a domineering manager. “He was my boyfriend for about six months and he never forgot it,” she says bitterly. “It must have been bliss for him.” The split widened when she took her “trash with flash” stage show to the London Palladium in 1978. The gaga audience held up placards reading “We love your tits.” Midler got carried away and “flashed my boobs–they were just being ridiculous and I was being ridiculous back.” Russo dressed her down violently backstage in front of Elton John. “I was very silly and wonderful, and he stepped on it,” she pouts. “He did things that were much worse than anything in the movie,” she continues. “He made my personal life so miserable that I became nonfunctional from 1973 on.” Midler dumped him a year ago, after he co-produced her movie, but still acknowledges that “he is a brilliant manager.”

Bette, who thrice has fallen in love “passionately, to the point where I was obsessed,” had a few post-Russo “hits and misses.” “Most guys figure that somebody small and buxom and blond with a strange nose and dancing eyes isn’t going to give them a good time in the sack. Which is the wrong way to look at it,” she observes. “People like me are the only ones who can give them a good time in the sack!”

For the past two years, though, she has settled in with actor Peter Riegert, who played the frat social chairman in Animal House, but met her while he was performing off-Broadway. “There was this guy with this beautiful face and this great body and these gorgeous eyes and this wonderful manner,” Bette recalls. She went backstage and said, ” ‘Well, let’s just go out for a little drinkie, what do you say?’ So we got drunk and I asked him if he was listed, ’cause I’d like to call him up. Sometimes I think I’m turning into a man, and it scares me,” she deadpans. “But since I met Pete, my life has been kind of quiet–not too many orgies, and we’ve been staying out of the hot tub,” she cracks. “I’ve been working on my craft.”

She’s promised fidelity (so has he), but marriage is not in the offing. “I would like to have children,” she says with her usual delicacy, “before my uterus falls out. And I think that when I decide I’ll probably reconsider the question of marriage.” As for women’s issues, she calls herself “not stridently feminist,” but then she adds: “White males, boy. They’re so full of shit they’re gonna get theirs from the Third World and from women.”

That tirade aside, she has become relatively domestic, renting Richard Chamberlain’s house in Los Angeles (“When you want limbo there’s nothing like it”), and has just bought a loft in New York’s hip TriBeCa area. There she plans three “dark and soundproof” bedrooms and a rehearsal studio. “I’m sort of nomadish, but I like New York.”

Money is okay, she says, but “I like charity. I want to give it away.” Indeed, Midler agreed that her Rose premiere be a fund raiser for New York’s Phoenix House, a drug rehab center. As for herself, Bette confesses: “I don’t do drugs. I have a devil. I don’t like to get stoned because then it comes out and I can’t control it and it’s very sick.” She admits, though, that “in my younger days I smoked a lot of reefers, but I lost my voice so I stopped. I gave a lot of great shows, though–unfortunately I croaked my way through them.” During her grueling Broadway run, she took an afternoon to do a performance for psychiatric hospital patients.

There is no truth to the rumor that she herself is in analysis. “That was market analysis,” she kids. “When I was about 19 I went in for a year, but I didn’t get very much out of it. I finally had to go to another shrink so he could tell me how to get rid of the first shrink.” She has had enough traumas to overcome. Her childhood in Hawaii as the only Jewish girl on the block was grim, and the family could never shake adversity. Her mother recently died of cancer, leaving her retired house painter father to tend her retarded brother; one of her sisters died in a freak car accident in New York’s theater district.

These days Bette yo-yos between cooking (“People come back time after time for my poached fish which I make once in a blue moon”) and dieting. “The juice-enema fast is one of my faves. I don’t recommend it for everyone, though.” She also does gymnastics and reads Bartlett’s Quotations. Midler is carefully pondering her next move, considering a “Rose Lives” tour or a venture into New Wave music. “Enough of this pussyfootin’ around,” she says, “I want to be a rock’n’roll singer.” The recently released Rose soundtrack has given a boost to her last LP, Thighs and Whispers, and next month she’s coming out with a book, a pseudo-memoir about a grand tour of the Continent, A View from A Broad. Other projects are an NBC special she’d like to call Greed, “guest-starring the Sylvers, Eddie Money and Johnny Cash,” and, of course, another movie. “When I was a newcomer, I laid back. Now that I have a little bit of knowledge, I kick ass,” says Bette, who reasons her star tantrums are acceptable “because I pay the bills.” With an audience now considerably broader than her original Continental Baths gay crowd, she is mulling a ’30s comedy, The Polish Nightingale, and dreaming of remaking Gypsy as Mama Rose. “I’d like to spend the rest of my life doing only characters named Rose. The Rose Kennedy Story, The Life of Rose Marie…” Bette is not sure whether her fate is to become “a nun on the altar of show business” or “a pompous and great American institution.” The fierce public attention hardly daunts her. “I hope they ogle me, goddammit,” she mocks. “What is all this for if they don’t?” And as for the problem of loneliness at the top, Midler snorts divinely, “It’s just as lonely at the bottom.”