THR

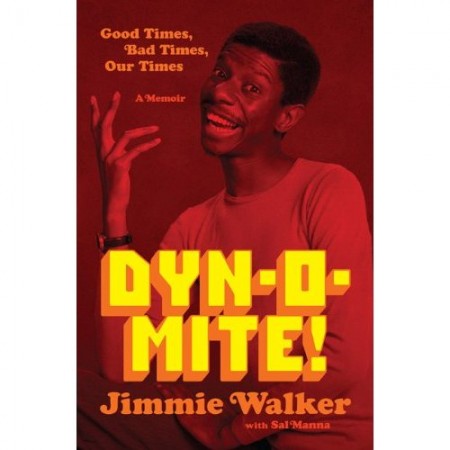

Dyn-O-Mite!

6/19/2012 by Andy Lewis

Jimmie Walker‘s illuminating, if uneven, new memoir reminds readers of his well-earned place in the pantheon of American comedy. Walker rose to fame playing J.J. Evans on the hit CBS sitcom Good Times (1974-79) and was a key figure in the comedy boom of the ’70s and ’80s with such friends as David Brenner, Bette Midler, Jay Leno, David Letterman, Freddie Prinze and Richard Pryor. Delving into the tricky terrain of race and Hollywood, he tells about going from being the official comedian of the Black Panthers to being “accused of ‘cooning it up’ ” on TV. “In the end I became too black and not black enough,” he writes.

The Bronx-born Walker stumbled into comedy in a post-high school War on Poverty-funded writing class for the unemployed. His first gigs were at Black Power rallies, and his early club act relied on material ripped off from Lenny Bruce and others and a smattering of original jokes like: “I’m from the ghetto. I’m here on the exchange program. You can imagine what they sent back there.” Such jokes scared TV bookers until friends like Midler and Brenner intervened. In 1973 — without an audition — Norman Lear cast the 25-year-old in Good Times, a Maude spinoff about a poor black family in the projects. Walker was the breakout star, and his catchphrase, “dyn-o-mite” — which Lear dismissed as a “non sequitur” — propelled the show into a hit. It also inspired a top 10 single, “Dynomite,” by one-hit wonder Bazuka in 1975.

Although initially praised by the NAACP, Walker soon found himself caught between a well-meaning Lear, who thought humor helped whites adjust to integration, and fellow castmember Esther Rolle, who attacked his character as “stupid” for giving the impression young blacks could succeed “standing on the corner and saying ‘dyn-o-mite.’ ” Walker defends J.J. as a “good kid who should have gone bad but never did” and deflects the criticism as coming from black expectations that pioneers needed “to be better ”¦ for progress.”

The book brings alive the comedy scene of the ’70s and ’80s. Walker was the first of his close pals to make it, hiring his struggling friends, and he recounts hanging with the young Letterman and Leno at his kitchen table brainstorming jokes and trading barbs. (Letterman was squeamish about sex; Leno just riffed on the others’ material.)

The book is uneven, marred by a shortness of style and a disjointed narrative — it is more a series of rambling stories than a cohesive memoir. Walker has become an outspoken conservative, dabbling in right-wing talk radio and going public about not voting for Barack Obama, and his odd political tangents can be skipped. Still, the book is more dyn-o-mite than dud.