Huffington Post

Whose Queer?: A Review of ”˜the 1970s: The Blossoming of a Queer Enlightenment’ at Leslie-Lohman

05/16/2016 11:16 am ET

By Christian Hendricks

Currently up in New York City is an exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay & Lesbian Art titled “The 1970s: The Blossoming of a Queer Enlightenment.” After visiting, I was disappointed, even irritated because it primarily contained two things: photographs of famous queers or famous queer locations (i.e. images of Harvey Milk and portraits by Mapplethorpe; documents of Stonewall and the piers), or drawings and paintings of nudity and erotica. To be clear, many of these works are beautiful in their own right; some I have admired for years. This is not a critique of the artworks themselves, but of the curatorial decision making. Exclusively displaying these two types of works essentially reduces the experience down to two basic feelings of nostalgia and titillation. The documentary photographs operate as pinned butterflies of activism and the homosex depictions as blunt symbols of sexual liberty.

Whose queer is this? Indeed, we are different because of our experiences and it’s probably true that these experiences of “difference” are frequently sexual in nature. And there’s no denying that the 1970s (a decade I can of course only know from the distance of history) were a period of sexual liberation which is proudly touted. Yet, despite all of this, the show still feels like a reduction of queerness in a museum of art dedicated to just that. The show feels more like a local history museum of a generalized sexual experience than an historical survey of how queerness blossomed in art.

As far as alternatives, there are of course the obvious, canonical examples of artists from the period that were also gay men: Warhol, Rauschenberg, Johns (the latter two were famously lovers). But they don’t have to be famous (noted: famous art is expensive to collect and exhibit), or gay males either. In fact – how exciting a show of lesser known, forgotten, or undiscovered queer artists from a generation past would be!

Beyond the sexual liberation in the 1970s, there was also the distinctly queer brand of counter-culture: a newfound opposition to marriage, monogamy, having children and other vestiges of heteronormativity. On the one hand you had the rise of punk, which was certainly not devoid of queers, and on the other was a new public advocacy for queer sexuality from the voices of people like Gore Vidal. What’s more, the voice of feminism was louder in the 1970s than ever before, providing an early platform for lesbian activism.

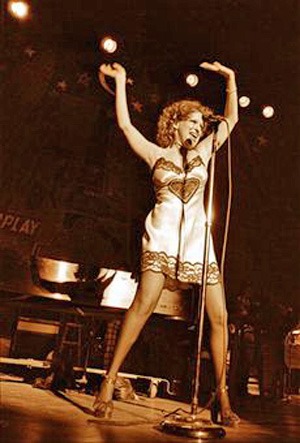

And what about artworks with nods to pop culture? Notably absent are any signs of influence from the 70s icons that were to become the dogma of our culture: Bette Midler, Grace Jones, Freddy Mercury, Joan Crawford, Divine, David Bowie – or virtually anyone else who became relevantly queer the moment their poster was pasted on the bedroom wall of a queer teen. These figures, who may not have been queer themselves, had the fashion, the attitude, or the story of struggle that resonated with a queer audience. Sometimes symbols of struggle are a better representation of queerness than queer sex itself.

An exhibition of note which successfully embodied the complexity of identity was the 1994 Black Male show at the Whitney Museum. In part because it was open to a plurality of identity – curator Thelma Golden took the black male identity as subject with a flexible, yet nuanced rubric for its rule over what was included. The show didn’t simply include works by black men (works by both black women as well as white men were included) or simply figurative imagery of the black male. It was a fuller, more considered approach to identity. An identity isn’t singular or static, it is complicated and fluid, and the representations must be as well.

This is the first exhibition I have attended at the Leslie-Lohman Museum, and in discussing this with friends who have attended previous shows, several have noted that this problem is nothing new at the museum. “It’s just the way it is.” While I have no intentions of launching an attack on this particular museum, I am compelled to speak out against the apathy and complacency which permit limited scopes of history.

If queer is in the eye of the beholder, as Vince Aletti has noted, then the beholding constituency needs a voice.

“The 1970s: The Blossoming of a Queer Enlightenment” is on view until July 3rd at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, 26 Wooster Street.