The Film Experience

Take Three: Barbara Hershey

Monday, May 16, 2011 at 2:06AM

Craig Bloomfield

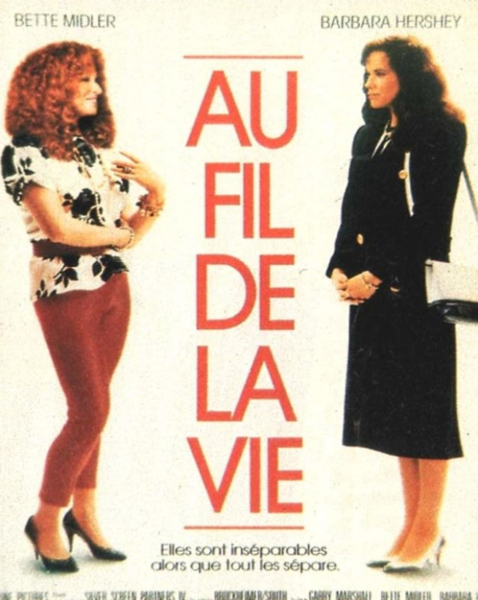

Take One: Beaches (1988)

Whilst Bette Midler played the brash, showy, let-it-all-hang-out role in Beaches, Hershey was required to provide the flipside, a more fragile, conservative, buttoned-up role. Of course, in Garry Marshall’s timeless, weep-inducing-yet-still-somehow-sickeningly-enjoyable sorrow-marathon emotional barriers are royally broken down. As a solidly played, unashamedly heart-rending and, at times (all times, in fact), downright sentimentally treacly showcase of female solidarity, it works, and works very well indeed. (The late ”˜80s was a fruitful time for the re-animation of such “woman’s” pictures; see also Steel Magnolias, Working Girl et al.) Beaches was a classic two-hander: one performance perfectly complemented the other. As the luxuriously-named San Franciscan heiress Hillary Whitney Essex, Hershey exuded just the right kind of well-turned-out class.

Her performance really was consistently good, despite the stock genre mannerisms very likely insisted upon by the filmmakers. She amiably chipped away at the inherent brittleness of the role, made her character appropriately timid, unexpectedly fragile and ”“ actually ”“ a believable mess with many of the concerns that spoke to half the women watching. (The other half would’ve surely identified with Midler’s character ”“ this is a large part of Beaches’ amiability.) As the requirements of the genre dictate, there are melodramatic turns aplenty ”“ love rivalry, career diversions, terminal disease ”“ and Hershey and co. revel in its cornball pleasures. In the process it gave Hershey her biggest exposure. It was a certified commercial platform on which she could do great work. She broke through the privileged whininess of the character and made such a prim, off-putting madam feel thoroughly deserving of our investment and sympathy. But didn’t Hershey look as if she wasn’t always best pleased to be the wind beneath Bette Midler’s wings?

Take Two: The Entity (1982)

Just recently Hershey’s made a bit of a re-emergence on the big screen in a couple of notable roles. Earlier this year we saw her add some major dramatic supporting greatness as the nervous-wreck mother in Black Swan (see below), for which she unfortunately missed out on a second Oscar nomination (her first and only nod so far was for Supporting Actress in 1997’s The Portrait of a Lady). She recently cropped up as a nervous-wreck grandmother in haunted house person flick Insidious, too. But it’s not the first time Babs has battled apparitions from the afterlife. Her career has seen its fair share of paranormal activity: back in 1982 she caused a spooky stir as beleaguered Carla Moran in Sidney J. Furie’s The Entity; a role for which should have earned her her first Oscar nomination.

Two years before the Ghostbusters zapped spooks left, right and centre, Hershey and her parapsychologists had to lure her spectres in with a fake house set-up and little more than a majorly unnerving atmosphere in order to trap the unnatural forces that have been pervading her home and her very being in frozen liquid helium. As you do. There are numerous scenes in which Hershey is laid flat out, being forced to participate in any amount of unfavourable activities. She gets put through the otherworldly ringer. It’s distressing viewing, but Hershey conveys a great deal of believable fear and anguish via her sincere performance. It was the first time she truly got to flex her considerable acting talents for prolonged periods on screen.

Take Three: Black Swan (2010)

Hershey was entirely perfect casting in Black Swan. She’s the right age, has the exact look befitting an unusual ballet-horror movie, is seasoned enough to convey the exact tone of her character (Erica Sayers, pushy stage mother and ex-ballet star ”“ I wouldn’t mention the term ”˜has-been’ around her) and fits well within the overall dark timber of the piece. She inhabits the role with requisite poise and gives great face, either swelled with fury, sincerity or girlish glee. To say she lived vicariously through onscreen daughter Nina (Natalie Portman) is pointing out the obvious. It’s a given that Erica is clearly not living better through displaced ballet from the off; the queasy, mechanical dependency she displays for Portman’s successes, hidden behind the dimmed light of motherly tenderness, gives Black Swan a lot of its freakish charm. The technical aspects go a long way in creating an aura of unease, but Hershey is the living embodiment of all the on screen fear that really terrorises.

Watching Black Swan again I began to question whether Erica actually does care what happens to Nina. Could it be that, all told, she’s acting in her own interests? Is she just a desperate yet pitiable witch just getting off on someone else replicating her former glories? Erica seemed to fix a permanent forced smile on her face, as if through her feverish joy she was hiding a knife behind her back. There are enough hints in Hershey’s demeanour, her perfectly awkward body language in the role, to suggest another slant to the character, an angle on which other interpretations could arise. Whatever the reading, it’s the very polymorphic nature of Hershey’s performance that fascinates. It also gives much weight to all the cries of ”˜she was robbed’ last February. But Hershey does tactical scariness well: whether she’s sitting in a darkened room waiting for attention, threatening madness via celebration-cake disposal or painting dodgy portraits whilst weeping, Hershey rules motherly ruin.

Three more key roles for the taking: Boxcar Bertha (1972), A World Apart (1988), Lantana (2001)