Winnipeg Free Press

September 21, 1978

She burst onto the scene after having established herself as one of the leading attractions at Manhattan’s Continental Baths. Now, Bette Midler, the queen of trashy pop, is about to parlay her extraordinarily diverse talents into The Rose, a film, she says with her convoluted sense of humor, that is “the sequel to Jaws, in which a shark is attacked by a great white woman.” Originally entitled Pearl and based on a female rock singer’s life as it revolved around drugs, drink and degradation, Midler and her manager-producer Aaron Russo emphatically deny the revised screenplay is the story of’the late, legendary Janis Joplin.

In the beginning there was this script entitled Pearl, which dealt with drugs, drink and degradation. It was a musical.

“Originally it was the story of Janis Joplin, which I wouldn’t do. But I told the people at Fox that if I could rewrite it, so the character isn’t Janis Joplin and the music isn’t Janis Joplin’s, and if I could give it a new story, then we might be interested in doing the film.”

Thus spoke Aaron Russo, whose baby is The Rose, the reconstituted Pearl, which will be released by 20th Century-Fox next spring. It does not deal with a shark, and it does not deal with Janis Joplin. It stars Russo’s real baby, Bette Midler, the extraordinary entertainer who only hopes that “I can portray Rose honestly. She’s such a sweet person.”

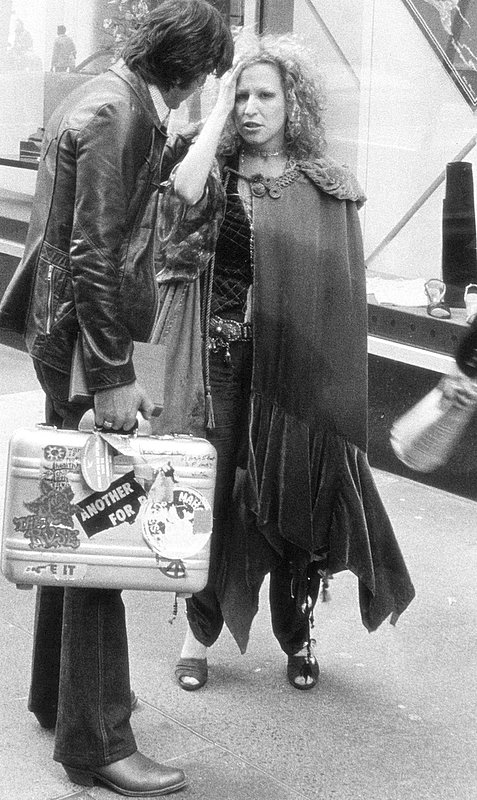

Something more than a polite spring shower was falling outside the New York Hilton the evening 20th Century-Fox took over the penthouse to honor both Bette Midler and the start of shooting on The Rose. In fact, it was a downpour. Yet those on the carefully screened guest list arrived in droves. The star recently had won over the town again in a series of performances at the Copacabana. And now here she was, up close, and curiously, causing whispers for the wrong reasons.

No one was repeating any of the outrageous bons mots that she might have been winging as she mingled through the crowd.

Indeed, it appeared she had none to say; nearly everyone received a cordial hello. Something was different, certainly in appearance. Peroxide and liquid protein had taken care of that. Gone was the electric red hair and sense of, well, ampleness. But gone, too, was her electric stage presence, and that was disappointing.

“Walt a minute,” someone said. “Is that Bette Midler?”

“This is me,” said the 32-year-old Midler, tugging at a long blonde curl. “And this is the way I’m going to stay. Blonde. Maybe.” She smiled, which turned her eyes into narrow slits. Then she puckered her lips, as if protecting herself from the next question.

Would she be doing another New York concert?

“For the movie? No. We were going to, but there wasn’t time. Now we’re going to do that out there.”

Out there? California?

“Yeeeeeessssss,” she said, batting her eyelashes in a parody of movie star.’

Was she nervous about making her first film?”

“Oh, this isn’t my first film,” she gasped. “I’ve never told anybody this. I never thought I’d have any reason to. But once I was an extra. 1 was an extra in The Detective with Frank Sinatra. And then I was an extra in – are you ready? – Goodbye Columbus. Thirty-two fifty a day and two hours on the train to and from New Rochelle to watch Ali MacGraw snap at the straps of her bathing suit.” Bette Midler made imaginary motions to snap at the tiny waistband of her jeans.

“Snap those straps, Ali. Snap that thing.”

“She wanted to be skinny for her movie,” offered Aaron Russo, her manager, shrugging his shoulders. “You want to know how she lost weight? She stopped eating. She’s also tired and a little nervous right now.”

So was Russo. Filming was to begin the next day in the penthouse, which would serve as the office of Rose’s manager. Cast and crew would remain in the city an additional 14 days and then would return to California for nine more weeks of shooting.

Locations on the West Coast would simulate Florida, where much of the movie’s action is set. “I don’t know what to think of first,” said Russo, who is producing his first film.

Bette Midler stands preening before a microphone. Behind her is her backup trio, the Harlettcs – “three examples of strictly non-kosher meat,” she tells her audience. The witty stage patter is just beginning.

The year is 1968. The place is the Continental Baths, the now defunct gay haunt on Manhattan’s West Side. From there to the penthouse of the New York Hilton in 1978 is a long trip, but Bette Midler has made it. She is big time, and her audience has grown from New York’s gay set to a nationwide following of hip and square.

In concert, the singer is an explosion of styles, ranging from Bea Lillie to Mae West to Liza Minelli to, yes, Janis Joplin. She can drop to the high school sentimentality of The Leader of the Pack as done by the ’60s group, the Shangri Las, then rise to the cool sophistication of a Noel Coward number.

But singing is only part of a Midler concert. She is a deft monologuist, with a breathtaking range of cultural references, from ’50s high school slang to Samuel Johnson. Between songs she zings in every direction oneliners, bawdy jokes, four-letter words, Long Island nasal accents (“Harry, did she really say that?”), and wilting insults (“It’s very 1971 of you to come in that dress”).

Even as Midler parodies – in songs or jokes – she evokes. She can draw from several second-rate singing styles to do one number, and yet make it uniquely her own. She can take trashy pop songs and transform them into something brimming

with emotion and power.

The gifts of Bette Midler – who has been called part Edith Piaf, part Sophie Tucker and part Belle Earth – once even prompted an essay in the unlikely pages of the New Republic. “It is Midler’s special appeal and inimitable strength of personality,” wrote the literary and cultural critic Richard Poirier, “that she can let herself satirize and be moved by what most of us want only to leave behind.”

Midler has turned out five albums, though her first – with such tracks as Am I Blue, Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy, and Delta Dawn – remains the most popular. The Midler audience tends to be urban and young, yet as eclectic as her material. She has appeared, minus knickers, to collect an award from Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Club, and on the Grammy television broadcast one year she wore a record single in her hair.

Her role in The Rose promises a no-holds-barred Bette, a larger-than-life personality in a larger-than-life art form. She plays Rose, a rock star who prepares for her concerts by swigging aquavit and banging a two-by*four against the wall to build up a sweat. She abuses men in much the same manner.

There is Rudge, her manager, who wears faded jeans and $400 lizard skin boots, and there’s Houston Dyer, a chauffeur she picks up one night and beds in a suite at the Plaza. She also once bedded with prim and proper Sarah, as well as, it turns out, her entire high school football team. “I hate mushy love stuff,” she tells Dyer during an embrace. “Wake me when the killing starts.”

Rose is vibrant, temperamental, Intuitive, and, above all, lovable. She has no home to speak of; she is always on the road. In the world, all she has is her music, her fans, her boyfriend, and her manager. And she thinks she has them all at her fingertips.

Midler’s theme song has long been Friends, a bittersweet number in which she eschews the sanctity of loneliness in favor of some sort of companionship. From the time she first sang that tune in the early ’70s, her companion has been the burly, 35-year-old Aaron Russo, always as her manager, and initially as her lover. The romantic relationship is no more, although, when Midler is near, Russo’s eyes never stray from her side, and when she is gone, his conversation is still filled with her.

“Wait till you see her on that screen,” says Russo, holding up his hand. “There’s only one person you’ll be able to compare her to. Chaplin.”

It was Russo – “I’m Jewish. Most people think I’m Italian”–who shaped the Midler career, guiding her –the nice Jewish girl from Honolulu – out of the Broadway chorus where, in the late ’60s, she was one of the daughters in Fiddler on the Roof, and into the Continental Baths. Very quickly, he would then take her into other clubs, on to the Johnny Carson show, and most important, on to records, on the Atlantic label.

“Some of the albums I’m not too crazy about,” Russo now admits. Her third album, Songs for the New Depression, met with a hostile reaction from critics and a less than enthusiastic response from the record buying public. “But Bette always bounces back.”

The Rose, a screenplay by Bo Goldman and Michael Ciniino (based on an earlier draft by William Kerby and a story by Worth and Cimino), is set in 1969. Says Russo: “Rose is a composite: Janis, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison –and Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. Characters who get too caught up in the momentum of their lives to know when to stop.” Nor is The Rose about Midler. “I’d tell her when to stop,” he says. “She’s emotional but not reckless.”

To solidify the sound of the picture. Worth and Russo have hired Paul Rothschild, the formal musical producer for Bonnie Raitt and, before her, the Doors, and yes, Janis Joplin.

The music for The Rose will not be middle-of-the-road “or even the eclectic stuff from Bette’s albums. It’s going to be out-and out rock,” Russo says.

Related articles