New York Times

February 2, 1990

Central Park‘s Tavern on the Green, where Bette Midler enacts perhaps a three-hanky version of the famous four-hanky ”Stella Dallas” finale, isn’t quite the right setting for this brave mother’s ultimate sacrifice. It was in a spirit of joyful self-abnegation that Barbara Stanwyck’s Stella, in the most famous scene from King Vidor‘s 1937 film, stood in the rain outside a grand hotel watching the wedding she could never attend, until a watchful guard shooed her away.

But the glass-walled Tavern on the Green is a wedding-watcher’s dream. Guards in Central Park at night have more pressing tasks than shooing away kindly, weeping mums. And most important, no mother today would see the wisdom of what Stella thinks she must do for her child. Even in 1937, there wasn’t a great deal of sense at the heart of this story.

”It seems unlikely that historians of the future will find Olive Higgins Prouty‘s ‘Stella Dallas’ among the imperishables of literature,” Frank S. Nugent wrote in The New York Times when King Vidor’s film (there had also been a 1925 silent version) opened at Radio City Music Hall that summer. Even then, Mr. Nugent noted, this 1923 novel was badly dated. ”On the practical surface of it, we cannot accept Stella Dallas in 1937. She is a caricature all the way.” Yet Mr. Nugent, in admiration, also said of this story: ”It has a tough old hide and only a tougher hide can be proof against it.”

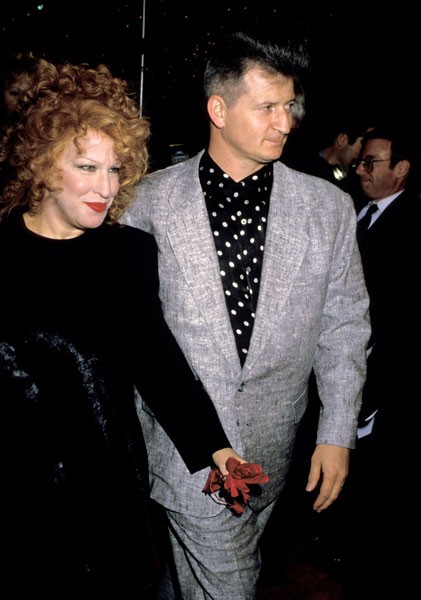

Fifty-three years later, the world has changed so drastically that the bare bones of ”Stella Dallas” don’t even begin to support this story. Single mothers are not unusual; class barriers are not unbridgable; little birds routinely fall farther from the nest. Yet it’s also true that the heart-tugging aspects of this mother-daughter drama retain their ability to bypass the brain, and that for the right actress the role of Stella remains a damp, soapy dream. Bette Midler, too old for the film’s opening and too smart for its resolution, isn’t exactly the right actress, but she’s a lot closer than might have been expected. Ms. Midler manages to gloss over the story’s inconsistencies, play up its charming aspects, and generally bluster her way through.

”Stella,” directed by John Erman and written by Robert Getchell, has an abbreviated title because its heroine skips a step and never marries. Stephen Dallas (Stephen Collins), the handsome, well-bred medical student by whom Ms. Midler’s feisty bartender has a child, is clearly not Mr. Right. In fact, he’s not even someone who could plausibly take an interest in the rough-edged and raunchy Stella Claire, were it not for the fact that she leaps to the counter of the bar and does a pantomime striptease on the night he happens to drop by. Does this kind of behavior indicate that Stella will wind up hiding her light under a barrel? Throughout ”Stella” many such questions arise, and audiences intent on enjoying the film would be well advised not to answer them.

One of Bette Midler’s real and unheralded talents is for camouflage, and her exuberance is most helpful in overshadowing the inconvenient aspects of this story. During Stella’s and Stephen’s courtship, Ms. Midler concentrates on showing off Stella as a great date; during her early years with little Jenny (played as a sunny, enchanting young woman by Trini Alvarado) she avoids questions about friendships, love affairs and job opportunities by concentrating solely on mother-daughter sweetness. And later on, as she prepares to steer Jenny toward the upper-class existence that ”Stella Dallas” unquestioningly embraces as a better life, she pointedly insists that this isn’t about money. Of all the thin ice that the film skates on, this is the thinnest by far.

Ms. Midler’s performance manages to be both involving and wildly inconsistent. The story is so full of holes that both she and Ms. Alvarado sometimes experience full personality changes from scene to scene. Why would the working-class woman who knows enough to tear the gold trim off her black cocktail dress, for fear of offending her patrician ex-lover, try to impress her daughter’s friends by dressing like Carmen Miranda? Why would she look like a biddy in a tattered old cardigan one moment, like a cowgirl in a mini-skirt the next? The irreconcilable character traits in ”Stella” aren’t even confined to the story’s two leads. As in the earlier film, the daughter’s young friends are kept away from her birthday party because Stella is a social outcast. Today’s teens, however, aren’t too housebound to drive past Stella’s window and drop their pants in rude salute.

In addition to Ms. Midler, who’s right to tackle this role with spirit, gumption and absolutely no shame, the rest of the cast is also strong. Ms. Alvarado, punkish in some scenes and every inch the debutante in others, brings a lovely, fresh manner to some of the story’s craziest extremes. Mr. Collins and Marsha Mason, as the film’s gracious bluebloods, manage to be attractive, disarming and not at all smug. And John Goodman, as the lovable blowhard who is Stella’s devoted pal, once again makes salt-of-the-earth sturdiness a scene-stealing trait. His deep, abiding and mostly unconsummated affection for Stella is the sort of thing that, along with Stella’s pure selflessness, makes sense only in movies, if even then. And only in movies like this. Tough hides, beware.

”Stella” is rated PG-13 (”Special Parental Guidance Suggested for Those Younger Than 13”). It has strong language and a few sexually suggestive scenes.