Refinery29

The Underlying Meanness Of The First Wives Club

KELSEY MILLER

SEPTEMBER 20, 2016, 10:00 AM

Remember when we all stopped saying “real women”? I don’t recall which trend piece woke me up to that shift in our cultural lingo, but I do know how fast it clicked. For most of my conscious life, “real women” had been the phrase used to describe women who weren’t models, who seemed relatable rather than aspirational, women who weren’t too hot or too confident but were, you know, normal gals. (And it went without saying that these were probably straight, cis women, too.)

“Real women” seemed like a helpful, friendly phrase, but of course the moment someone pointed out that all women are real women, I got it – and instantly tossed that term out the window. Odd how something that once seemed useful and even empowering can reveal itself as exclusionary and offensive when you take a closer look.

I thought about the real-women problem a lot while second-glancing The First Wives Club. I saw this film for the first time at the age of 12 with my dad in a local suburban multiplex. We both laughed, but at times he seemed a little squirmy. Walking out of the theater, he sighed in quiet disappointment: “I just wish it wasn’t all about hating men.” At the time, I thought my dumb old dad just didn’t get it. Because, uh, it wasn’t even about men. It was about women – real women – standing up for themselves and each other. It was about unity and self-actualization, and also it was just a really good, funny movie. They sing in the end!

As I turned on the film a few weeks ago, I remembered my dad’s man-hating comment, now seeing it differently. He must have felt so threatened, so defensive in the face of such unapologetic feminism, I thought. This movie came out in 1996, back before Roxane Gay and Lemonade, when people still made bra-burning jokes about feminism. This comedic opus of real womanhood must have been a shock to his deeply un-woke system. The opening titles continued as Burt Bacharach’s “Wives and Lovers” plays in the background, an obvious satire: “Hey, little girl/Comb your hair/Fix your makeup/Soon he will open the door/Don’t think because/There’s a ring on your finger/You needn’t try anymore.” Twenty minutes in, I’d all but decided my father was an MRA – when I realized I was squirming myself.

An early scene in the film unites all the first wives, Elise, Brenda, and Annie (Diane Keaton), having lunch after the funeral of another first wife, Cynthia. Cynthia committed suicide after being left by her husband for a younger, blonder model, and these three women are in the same boat: fortysomething, newly single, and therefore with little left to live for. (“Bye bye, love. Hello, Pop-Tarts.”)

“What’s her name?” asks Elise (Goldie Hawn).

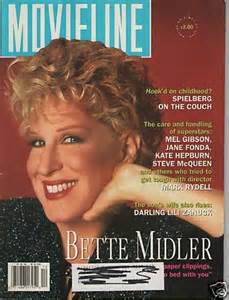

“Shelly,” replies Brenda (Bette Midler). “Shelly the barracuda. She’s 12.”

Haha! They’re so real and relatable! They’re drunk and angry and victimized (and rich and white). And who is to blame? Men, yes, duh. But mostly other women – the fake kind.

There’s Phoebe (Elizabeth Berkley), the young actress with whom Elise’s husband ran off. She’s blonde, big-eyed, and so evidently stupid that she’s almost incapable of basic human interaction. She claps her hands with fingers splayed like a toddler’s and runs back and forth in high-heeled shuffle steps, the live-action version of a Blondie cartoon. Her most memorable line happens when a doorbell rings and she throws her arms in the air, shouting, “Pizza!” Oh, and spoiler: She’s 16.

Then there’s Dr. Leslie Rosen (Marcia Gay Harden). At the start of the film, we learn she’s a therapist, treating both Annie and her estranged husband, Aaron (Stephen Collins – more on that doozy later). Perhaps an iffy professional move, but clearly she’s no bimbo; she’s a doctor. Strong, intelligent, professional woman? Ten feminist points! But then – twist – it turns out she’s also sleeping with Aaron behind Annie’s back. And, while we’re at it, behind the state licensing board’s back.

If Phoebe is the ditz, then Dr. Rosen is the vamp, and both women, once villainized, pretty much vanish from the film.

Finally, we have Shelly (Sarah Jessica Parker). This is the aforementioned barracuda who apparently stole Brenda’s husband, Morty (Dan Hedaya). In terms of the villains, she gets the most character development – meaning she personifies multiple traits of the Evil Husband-Stealing Archetype, rather than just one. She’s not literally 12, but she is very young, thin, mean, and ditzy. She’s a legit gold-digger who slinks around in furs and picks her teeth at the dinner table.

Parker, to her credit, gives as much possible dimension to this monster (if there’s an upside here, it’s the reminder that SJP has mean comedic chops). But more than anything, Shelly serves to expose the meanness underlying this whole film. At one point, Brenda runs into Shelly and Morton in a women’s clothing store. Shelly emerges from the dressing room, clad in a black slip dress.

“Shelly, look at you,” says Brenda. “My my, the bulimia certainly has paid off.”

Shelly replies: “Brenda, why don’t you try these on” – here she spreads her arms wide and lowers her voice to a trollish grunt – “in your size.”

I get it. We’re supposed to hate Shelly for making her mean little fat jokes, and we’re supposed to laugh and high-five over Brenda’s bulimia burn. But they’re both shitty jokes because both these characters are composed of shitty female tropes. Just as Shelly’s thinness and beauty make her fake and hateable, Brenda’s chubby frump look makes her real and relatable.

The other two main characters are defined by old-school ideas of womanhood as well. Annie is a doormat who crumples under conflict. Elise is vain and insecure, clinging to youth with her French manicure and drinking herself to sleep under a self-portrait. Theoretically, they’re supposed to shed these old personae and become their best selves when united. That’s what all the montages and musical cues would have you believe, certainly. But really, Annie hits the nail on the head when she declares, “We are the three witches!”

Before sitting down to rewatch The First Wives Club, I was prepared to cheer it on as an outlier among the comedies of its time. I didn’t want to find fault in a film I rented dozens of times as a child and bonded over with friends in college. I can see the collective internet rolling its eyes and hear its snarky voice in my head saying: Girl, this isn’t Sophie’s Choice. You’re taking it too seriously. Maybe it’s right. Maybe I’m just being a killjoy. But that voice sounds a lot like the one that wants to make excuses when Amy Schumer posts a racist tweet (she’s joking, Jesus), or conveniently forgets about Woody Allen’s personal history when Annie Hall comes on.

From the first bad joke onward, it was like watching the film die by a thousand tiny cuts. One might overlook a few, but the dialogue is jammed with more eating-disorder jokes, gay jokes, plastic-surgery sight gags, and stereotypes galore. (The entire Brenda/Morty subplot manages to roll both Jewish and Italian stereotypes into one lousy storyline; it’s almost impressive.) There’s dated, and then there’s dated beyond repair. As if to underscore this fact, there’s Stephen Collins, admitted child molester, in one of the lead roles. Sometimes you can’t just suspend your disbelief. Sometimes you shouldn’t even try.

But these one-off moments are little more than icing I could try to scrape off if the cake itself weren’t so lousy. The First Wives Club presents itself as a story of sisterhood, and in the end we’re supposed to watch these women emerge as their own champions. And it almost, almost happens that way! Elise, Brenda, and Annie eventually realize they’ve been too wrapped up in their own vengeance and should instead focus on the greater good. Huzzah! So they’re going to open a crisis center for women. Great! And how are they going to do it? By blackmailing their ex-husbands into paying for it!

I mean, shit. I guess a crisis center is better than no crisis center, even if it is bankrolled by three unwilling ex-husbands (one of whom is a statutory rapist and another of whom has committed major financial fraud – but enough about that, oh well!). It’s just kind of a bummer that in the end it’s not really these women but money that saves the day. And it’s not even their money.

Yes, my dad was right that there is man-hating in this movie. But the movie itself seems to hate women more than anything. Under the guise of unity, it pits women against each other (in a fight over men, no less). Like the phrase “real women,” it excludes and demeans everyone who doesn’t fit politely into an archetype. And, comedy or not, why shouldn’t I take that seriously? Should I just wince over the icky parts and go along to get along, wait until that killer song-and-dance finale and sing along? Maybe. Maybe it’s okay to have my cake and eat it, too; it is just a movie, after all. But, really, is it so much to ask that we make a better cake?