Posted on Fri, Feb. 06, 2004

Something borrowed

BY EVELYN McDONNELL

I’m in the Mood for Love and I Only Have Eyes For You are two standards from a time when men in Italian suits, not blue jeans, ruled the mic. They’re swing ballads, sentimental affairs created for strings, horns and crooners, not guitars, synthesizers and shouters. So what is Rod Stewart, one of rock ‘n’ roll’s definitive singers, doing singing them on his latest CD?

”They don’t write them like this anymore,” Stewart, 59, answers, over the phone from Los Angeles on a recent winter day.

It’s the kind of thing a parent says, speaking from the wrong side — the exchanging-relevancy-for-nostalgia side — of a generation gap. So when an icon of the g-g-g-generation that was supposed to die before it got old says it, he is being somewhat intentionally ironic. Which doesn’t mean he’s not also sincere.

”There’s a lack of melody in contemporary music,” says the singer of classic-rock staple Maggie May and ersatz disco hit Do Ya Think I’m Sexy. (Stewart opens his U.S. tour at the Office Depot Center tonight.) “There just aren’t any Beatles anymore, or any Motown-era stars, writing those powerful songs that will be with us for the rest of our life. Today’s music is instantly forgettable.”

The millions of people running around with Kelis’ Milkshake and OutKast’s Hey Ya latched in their heads would beg to disagree with old-fogey dismissals of today’s songcraft. But there’s no denying Stewart has hit a nerve: It Had To Be You: The Great American Songbook, his 2002 CD featuring tunes by such classic 20th century songwriters as Hoagy Carmichael and Cole Porter, has sold 2.3 million copies in the United States alone.

The album has inspired a range of artists, including Cyndi Lauper, Michael Bolton and Caetano Veloso, to excavate pop’s past for current treasure. Spanish singer Sonia Santana is releasing an album of Latin classics from the swing era, sung in English and Spanish. Even on American Idol, pierced teenagers sing Burt Bacharach tunes.

Is all this digging around in the past a healthy reclamation of America’s musical heritage, or the rock-star equivalent of burying one’s head in the sand?

20 YEARS IN MAKING

”I’ve been wanting to do this for 20 odd years,” says sometime South Florida resident Stewart (he spends a couple of months every year at his Palm Beach waterfront mansion). ‘But Warner Bros. was never interested. They saw me only as singing rock ‘n’ roll stuff, which I love. They didn’t see the old songs as being worthwhile.”

The singer got his chance when his relationship with Warner Bros. ended. He took his recordings of old standards to J Records head Clive Davis. It Had To Be You was followed by As Time Goes By: The Great American Songbook Volume II. Volume three is in the works.

”I was shocked myself I remembered so many of the melodies,” Stewart says. “I don’t know how on earth I got to know these songs. They entered my subconscious when I was a kid.”

How could one forget a song like They Can’t Take That Away From Me, covered by Stewart on It Had To Be You? The Gershwin composition revels in romance, rhyme and style (not unlike several tracks on OutKast’s new album): ”The way you wear your hat, The way you sip your tea, The memory of all that, No, no! They can’t take that away from me!” Stewart’s voice, lower and warmer since a throat operation a few years ago, fits the tune’s easy swing nicely. The track is, almost, irresistible.

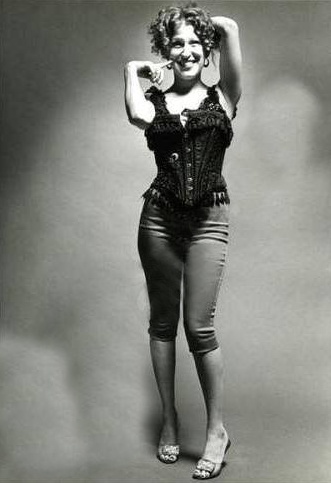

”There’s been a yearning for melody for the last 20 years,” says Bette Midler, who last fall released Bette Midler Sings the Rosemary Clooney Songbook and will perform Feb. 28 and 29 at the Office Depot Center. ‘The beat took over the melody; melody took a beating. People are looking for lyrics that are enchanting to them. And for music they discarded when they were teens because they discovered rock ‘n’ roll.”

RHYTHM’S ONSLAUGHT

There’s no denying rhythm has aggressively asserted its place in today’s Hot 100. Hip-hop and R&B dominated the charts in 2003. But beat has always been crucial to American pop. Even in Duke Ellington’s day, music didn’t mean a thing if it didn’t have that swing. Fifty years from now, Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, the production and songwriting team also known as the Neptunes, may rightly be regarded as the Leiber and Stoller of today’s chapter of the American songbook.

Not that the gray-haired set should be expected to appreciate Hot in Here (especially after Nelly’s Super Bowl performance). Ultimately, old rockers’ shape-shifting says as much about the aging of the CD-buying public, and the changing sound of radio, as it does about the state of songwriting.

”With the consolidation of radio, stations all play the same thing,” Midler says. “It’s a terrible thing for music. People past a certain age don’t listen to it. There isn’t any music for them.”

AGING HIPPIES

Stewart blames the decline in appreciation of jazz standards not merely on today’s music, but on the ’50s and ’60s. ”No one wanted to hear these songs anymore,” Stewart says. “Rock was brand new and spirited. It gave teenagers an identity away from their parents.”

Pop music rejuvenates itself with periodic rebellions. The so-called Oedipal complex — the desire to kill, or at least overthrow, one’s father — is the engine of much cultural change. Chuck Berry told Beethoven to roll over; hippies hated The Man.

Of course, by the ’80s, those same baby boomers had become the establishment. Public Enemy denounced Elvis Presley; Slackers told yuppies nevermind.

So what’s a middle-aged pop star to do but throw it in reverse? Call it the Bush complex: Junior becomes Daddy. Stewart began humming the tunes that had slipped into his subconscious. As the saying goes, we all become our parents.

YOUNG OR OLD?

Which begs the question of who, exactly, has run out of creative steam. What right do the singers of old songs have denouncing new songs as ”instantly forgettable”? What ineffable tunes have they crafted lately?

Stewart’s albums have been roundly and rightly slammed for their smooth-jazz, middle-of-the-road arrangements. Part of the appeal of the standards is their straightforwardness: Unlike today’s hits, these riffs aren’t deconstructed with samples, scratching and remixes. Stewart’s versions, cutting out the instrumental breaks and big-band sound, simplify the tunes even more.

”We came up with a brand new clean deal of doing this,” he says. “There’s hardly any playing or jamming: just my voice and the four-piece band and strings.”

The singer shrugs off criticism. ”You can’t please everybody,” he says. ‘A friend of mine says, `I can’t put on those old records when I’m with a girl, but I can put you on and still feel hip.’ ”

Midler shows impeccable taste paying tribute to the late Clooney. She also is very wise not to want to be competing against the singer of This Ole House and Come On’A My House for the best pop album Grammy, for which they are both nominated.

BRIDGING THE GAP

Clooney was a friend and mentor to Midler. ”You rarely come across a musician who’s so kind,” Midler says. “And so anxious to help someone. She kept up. She loved musicians and people who loved music.”

Despite their age difference, no generation gap separated the singers, perhaps because Midler was never a rock rebel, but a pop entertainer. Maybe, if she gave them a chance, Midler would see that today’s post-rock artists are also not, as she says, “disposable.”

There’s more than a little Midler in a brassy, complicated drama queen like Kelis. Both, primarily as singers but also as writers, are making their own contributions to the great American songbook, chapter and verse.