Daily Herald

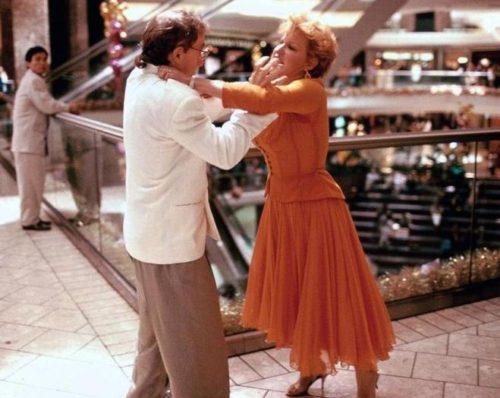

Woody and Bette’s affairs push wedded bliss to the limit in ‘Scenes From a Mall

February 22, 1991

In “Scenes from a Mall,” Woody Allen becomes irate, hauls off and smacks a mime right in the chops And the poor guy never says a word.

It’s a major moment in the Woodman’s acting career. He actually appears to be versatile. This marks the first time in 15 years (since “The Front”) that Allen has acted in a movie directed by someone who wasn’t him. Now, thanks to director Paul Mazurksy, Allen’s image as a fumbling, nerdy New York intellectual has been expanded into a fumbling, nerdy New York intellectual who can actually get mad and hit people.

“Scenes from a Mall” is not a wholly successful movie. We get rehashed L A jokes – mostly celluar phone and personal beeper gags – that have been delivered with far greater satirical skill by Steve Martin‘s “L A Story.” Although relatively brief for a feature film, it stretches the subject matter far too thin. After a while, we begin to think

the main characters have been in this mall for most of their 16 years as man and wife.

But what an irresistible idea – Woody and Bette Midler as married professionals who go shopping for party goods and wind up buying a comic package of painful self-discovery and rekindled romance. “Scenes from a Mall” isn’t exactly

lowest common-denominator material.

It addresses mature viewers who’ve racked up a few years of experience in the marriage department. The characters played by Woody and Bette, Nick and Deborah, have been married 16 years (plus one year of living together).

During the few hours they spend at an L A. shopping mall (in reality the Stamford Town Center in Stamford, Conn.), Nick and Deborah delve into the foibles and self-deceptions that come with a too-comfortable middle-class relationship after such a long time.

Nick (Woody with a trendy red ponytail ‘) works as a high-powered sports attorney who represents athletes in commercial deals. Deborah, a psychologist, has just written a best seller about the secrets to keeping long-term marriages alive.

While doing some last-minute shopping for their big party, Nick and Deborah make the rounds of the mall, indulging in rather innocuous self-congratulations about how they’ve remained a happy, f a i t h f ul couple while all those married people around them have become divorce statistics.

Nick, however, exhibits an ever-soslight anxiousness through his words, foretelling the moment when he nonchalantly drops a hand grenade into the conversation.

He’s had an a f f a i r. Actually, two affairs. Three, if you count the hooker in Dallas. The abrupt announcement generates a predictable, slowly simmering explosive response from Deb o r a h. And Midler generating an explosive response on the screen is like witnessing a nuclear chain reaction.

From then on, we watch as these two deceptively once-happy people begin to dismantle their relationship, analyze their needs and wants, then vacillate between patching up their rocky boat or allowing it to sink. First it goes one way, then a surprise development sends it spiraling the other direction A sudden twist of events saves it, only to have

it be hurled backward by continuing revelations of impropriety and lies.

“Scenes from a Mall,” written by director Paul Marzursky and Roger L. Simon, is driven by f u n n y, unsettling truths about love and marriage. (As a person married for 16 years, I can attest that many of Nick’s ambivalent observations about this most hallowed of human institutions ring with needling perception.)

The filmmakers approach “Scenes from a Mall” much like a modernday Greek tragedy in which the welloff protagonists achieve wisdom through great s u f f e r i n g. Three groups of traveling minstrels – an a capella Christmas choir, an L.A rap group and a Spanish ensemble – serve as musical Greek choruses, singing songs that underscore Nick and Deborah’s constantly changing frames of mind.

These groups are integrated into the story much better th;m the mall mime (played by the a m a z i ng d a n c e r / p e rf or m a n ce a r t i st B i ll I rwin). He’s the omnipresent clownish figure in the background who c o n s t a n t ly m o c ks N i c k ‘s overwrought state.

Irwin is sheer joy to w a t c h, but after a few pieces of shtick, the mime begins to hit us over the head too intensely with the idea that love makes clowns of us all.