Wisconsin State Journal

October 28, 1979

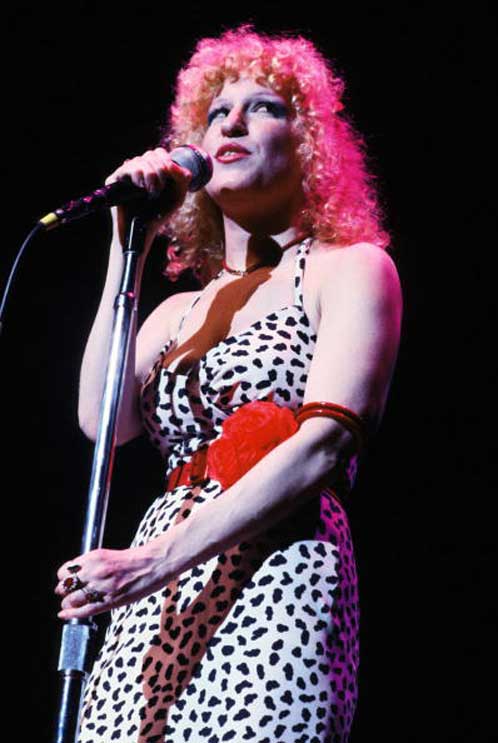

Flaky singer of raunchy songs breaks out of her stereotype in a dramatic, emotional movie that could win her an Oscar

Next month Bette Midler, 34, darling of the gay set, makes her film debut as a leading lady in The Rose, a $9 million 20th Century-Fox production inspired by the tragic life of the late Janis Joplin, a rock singer from Port Arthur, Tex., who overate, overdrank, oversexed and eventually overdrugged herself to death in 1970 at age 27.

Midler’s performance as Rose is so electrifying, so shattering, so geometrically intensive (she throws herself away with such knowledgeable abandon) that the picture’s end finds the viewer physically limp and emotionally depleted–but firmly convinced that this tiny (5-foot-1), carrot-topped actress will surely be nominated for an Oscar for her portrayal of a rock singer who “lived fast, loved hard, died young and left a beautiful corpse.

The Rose is no great shakes as a motion picture, but Bette Midler’s performance is virtuoso, and the Hollywood crowd is convinced that she is the successor to Barbra Streisand. To date, three major studios are bidding for her next film.

Onstage, Bette (who was named after Bette Davis by her star-struck mother) is noted for her profane language, her off-color jokes and her > myriad of musical vocal styles, some of which she uses like aphrodisiacs to stimulate her audiences into stomping, stamping, screaming, groaning, whistling and yelling. But in the privacy of her Beverly Hills home, she is so demure–such a stereotype of the librarian with horn-rimmed glasses who desperately wants to land a husband–that one finds it difficult to believe she was “discovered” a decade ago singing raunchy parodies at the Continental Baths in New York City, where she became a legend of sorts.

“Offstage,” confides Bette (pronounced Bet), “I am basically a serious, sentimental, frequently maudlin person–the complete” opposite of the wild, zany hedonist I play onstage. I’m really two people, a schizoid personality. Look at me. I wear glasses. I look like a librarian and behave like a schoolteacher, which is even worse.

“You ask me what I want out of life. I’d like to be happy with myself, which I’m not. There’s a kind of nameless discontent, a dissatisfaction which always seems to be with me. I guess I’d like a husband and a house of my own. I’m always renting. I’ve been out here in Los Angeles for three years now, renting other peoples’ houses. I get caught up in so many projects that I don’t have time to buy one for myself. If I did, I’d buy one in New York. I lived there for lO years in a little dump of a flat on Barrow St. [in Greenwich Village]. I was very happy there.”

Bette Midler, one of four children of Ruth and Fred Midler, was born and reared in Aiea, a working-class Samoan district of Honolulu–the only Jewish girl in the neighborhood. Her father, a house-painter attempting to flee from a domineering mother, moved his family to Honolulu in search of “a paradise he is still searching for.” Her mother died of liver cancer last year.

Always and still unhappy with her looks, Bette escaped into acting in high school, majored in drama at the University of Hawaii for one year, then worked on a pineapple cannery assembly line. In 1965 when George Roy Hill was directing James Mtchener’s Hawaii in Honolulu, she was hired to play a missionary’s wife. The job paid $350 a week and took her to Hollywood, from where she sped to New York “to make it as an actress.”

“I was a speedy little person with endless energy,” she recalls, “and I never stopped running. I worked as a go-go dancer in Union City, N.J. You had to beat the guys off with a club, but that was my happiest job. I love to dance, to move. I worked at jobs in the daytime–typing and filing, selling gloves at Stern’s department store.”

She found work in Off-Broadway revues, sang for experience in clubs and restaurants, finally landed a chorus part in Fiddler on the Roof, then graduated to the role of Tevye’s oldest daughter, a role she held for three years on Broadway.

Then came the Continental Baths, her “Divine Miss M” act, and a recording contract. Personal appearances in big-name clubs and theaters soon followed, and gradually Bette Midler practitioner of camp, burlesque, parody, call it what you will –developed into a major stage entertainer.

Helping in her rise–as Sid Luft once helped Judy Garland and Marty Melcher helped Doris Day–Aaron Russo, son of a Manhattan lingerie manufacturer, appeared on the scene in 1972 to become Bette Midler’s agent and amour. Their entente dissolved a year ago, and Bette has since taken Arnold Stiefel as her new agent, Gerry Edelstein as her lawyer, and an actor as her new lover.

It was Russo, however, who first suggested in 1972 that Bette star in a film based on Janis Joplin’s life.

“I had seen Janis Joplin work one time,” she explains, “and I had also seen Clara Ward and Tina Turner work, and I could understand how each of these women projected their energy into turning crowds on, and I wanted nothing to do with that.

“I think they first gave me the movie script after Janis’s death, but I didn’t want to be associated with that kind of necrophilia. But they kept after me. Aaron, who was my manager at the time, said, ‘You really ought to do it.’ But I’m very stubborn. I kept saying, ‘No, no, no.’ Finally they sat me down and said: ‘This picture offers you a great range

of possibilities. You can make people laugh, you can make people cry, you can sing and be funny and everything. And in the end you get to die. What could be better for an actress?’ I finally saw the light, and it sparked me off. But for a long, long time, I really didn’t care for it. But when I committed myself, I gave it everything I have. That’s the way I am.”

Since so many of the rock stars of her youth–Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Elvis Presley–succumbed to drugs, I asked Bette why such performers were compelled to dose themselves.

She reflected for a moment, then explained: “Because it’s the only way to feel normal when you’re on the road, working that kind of music–which I didn’t know before, because I usually sing sort of ballads. My act is ballads and swing music and a little bit of rock ‘n’ roll. I’ve never sung an hour and a half of straight rock ‘n’ roll. I had no idea until I did The Rose how much it hurts your body. I had backaches and legaches. I was in a lot of physical pain after doing a couple of shows.

“I think that’s part of the drug bit–the fact that the pace is very fast and you get very, very worn out. And in order to feel like you’re okay, you take things. You ingest uppers or downers–uppers to keep going, downers to fall asleep. The pace is very frantic, and it’s self-fulfilling. The pills make you feel okay for a while, but then the effect wears off, and you need more. It’s a vicious circle of doom.”

“I’ve never had to work the way some of the rock ‘n’ roll people do. I’d like to, just to see what would happen to me under the circumstances, because I’m not a big druggie. I never was. I don’t think I could go at that pace. I think I would just try to pace the shows so that I wouldn’t have so many in a row. You know what I’m saying? I mean, so many one-nighters, moving from place to place, the motel life, the motel food, the lack of sleep, the jam sessions and all that stuff. It’s a real killing pace, and it’s not for me.”

So what is for Bette Midler? Another road tour, a book about life on the road “which I wrote and is scheduled for publication in February, and hopefully a growing career in motion pictures.” Also, as afterthoughts: “I’d like $20 million, which would make me feel secure, and a husband who is intelligent, witty and good in bed.”