The Telegraph

Cheeks to die for: the tragedy of the writer behind

The First Wives Club

By Susannah Goldsbrough

7 September 2021

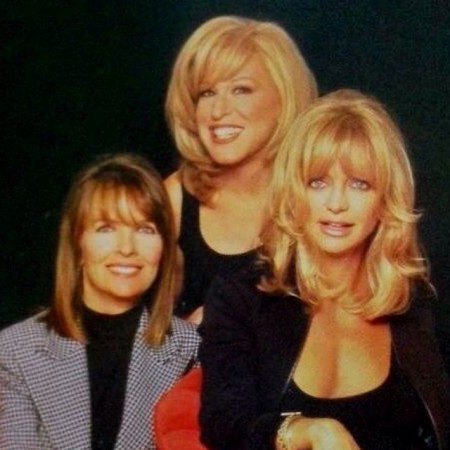

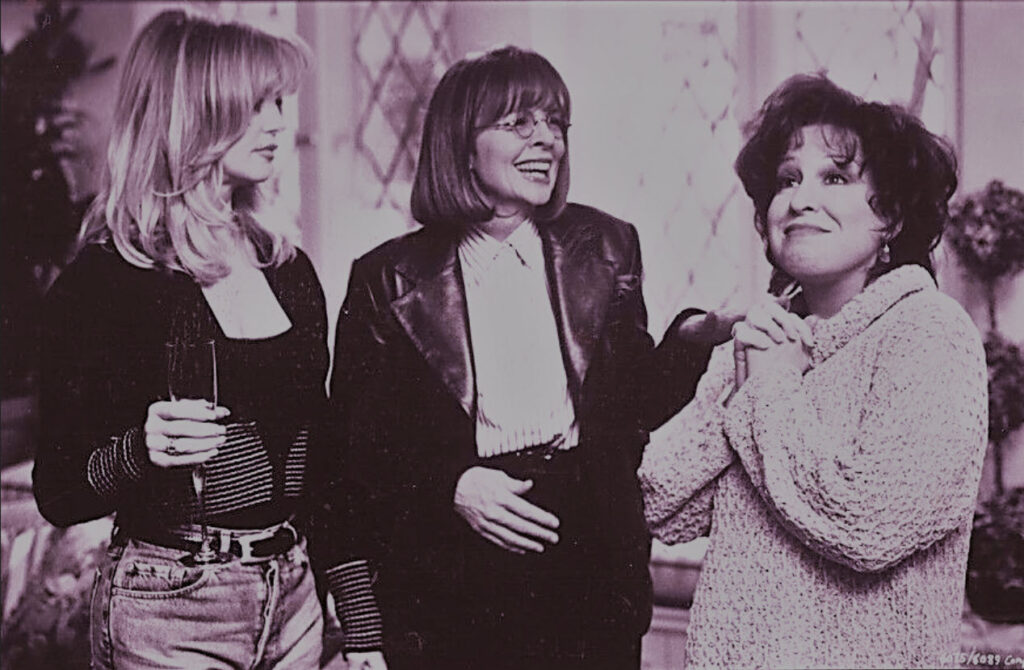

“Fill ’em up,” growls the fictional film star Elise Elliot in an early scene in The First Wives Club, through pouting lips that look not so much bee-stung as shot full of venom. Despite her plastic surgeon’s ill-disguised exasperation – “Elise, if I give you one more facelift, you’re gonna be able to blink your lips!” snaps Rob Reiner – the plastic surgery-addict played by Goldie Hawn in the cult 1990s revenge-fantasy film is not about to take no for an answer.

It’s a very funny scene, but one that real-life tragedy has saddled with a bitter aftertaste. It was Olivia Goldsmith’s 1992 novel of the same name – about three middle-aged friends who decide to get their own back on the good-for-nothing husbands who have left them for younger women – that inspired The First Wives Club, released 25 years ago this month. But in 2004, Goldsmith herself would die while undergoing a chin tuck.

Goldsmith, a best-selling writer many times over, who specialized in slick, engaging plots that delivered punchy feminist messages, had checked into the Manhattan Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital in early January for a minor surgical procedure. She’d already undergone several, all with the same well-respected surgeon. But she opted for general anesthesia, which comes with risks and which the procedure does not require. Four minutes after it was administered, Goldsmith fell into a coma. She was transferred to Lenox Hill hospital, where doctors worked to revive her while friends gathered at her bedside. Eight days later, she died.

How ironic that Elise, in part a fictionalized version of Goldsmith, eventually abandons her Botox-buoyed quest for youthful film roles in favor of a decorated stage career and a greater sense of personal fulfillment. The tragic fate of her author plays out like a bleak alternative ending to an uplifting feminist film.

First Wives Club starts off as a boisterous and slapstick revenge spoof but develops into a moving midlife coming-of-age drama. The story begins when three old college friends – pushover Annie (Diane Keaton), whose husband is sleeping with their therapist; financially struggling divorcee Brenda (Bette Midler); and alcoholic actress Elise (Hawn) – reunite at the funeral of the fourth member of their posse, Cynthia (Stockard Channing), who had thrown herself from her penthouse balcony on the day of her ex-husband’s remarriage.

Realizing that they have all been abandoned by their husbands in favor of younger women, the trio vow to avoid Cynthia’s fate at all costs by banding together and wreaking terrible destruction on their philandering exes.

So begins a revenge plot that takes them from the drudgery of housewifery to the glamour of New York high society (Ivana Trump, in a cameo, delivers the film’s most famous line: “Don’t get mad, get everything”) via a gay bar, a kidnapping, and a death-defying multi-story plunge in a piece of scaffolding. Along the way, they find self-acceptance.

“The funny thing was that by the time we had our husbands where we wanted them, revenge didn’t seem so important,” says Keaton’s character Annie, as the film draws to a close (although not before it gives us a glorious three-woman rendition of Lesley Gore’s feminist anthem, You Don’t Own Me). It is a message that, unlike Elise, has aged with natural grace. How poignant that its creator died trying to reverse time’s effects.

Goldsmith based the story on her own acrimonious divorce from business executive John T Reid. “He got the house in the Hamptons and the co-op and the Jaguar… I got nothing,” she told The New York Times in 1996. At the time of the separation, she was a high-flying New York management consultant – one colleague said her success was the result of her “rather extraordinary” abilities as a salesperson – but broken and dejected, she moved to London, changed her name to Justine Rendal, and wrote The First Wives Club.

So taken with the story was Sherry Lansing, an executive at Paramount Studios, when she read the manuscript in the early 1990s that she bought the rights to it before Goldsmith had even secured a publisher. “It was one of the single best ideas for a movie I’ve ever heard,” she told The New York Times.

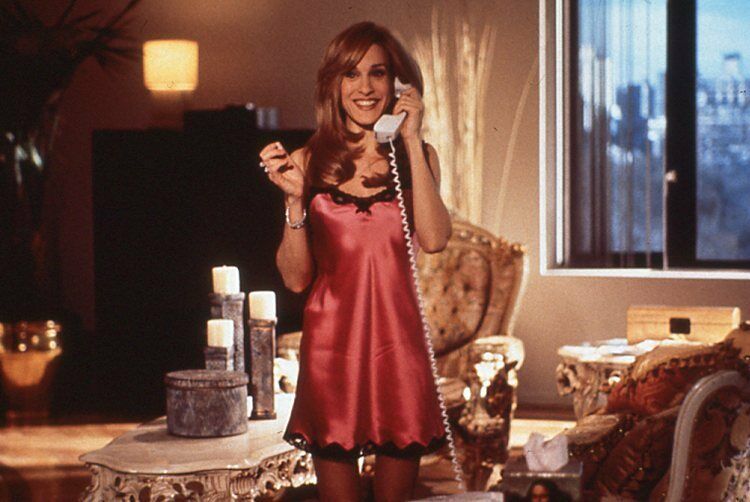

Her instinct was rewarded: the film made $18.9 million on its opening weekend, topped the box office for three weeks, and eventually grossed over $180 million worldwide on a budget of $26 million, thanks in part to an all-star cast that included Maggie Smith, a cameo from Gloria Steinem, and Sarah Jessica Parker in her breakout role.

But back in 1995, when she became chairwoman of Paramount and handed the project to Hollywood super-producer Scott Rudin, things didn’t look quite so rosy. Dissatisfied with Robert Harling’s screenplay, Rudin took the script to his friend screenwriter Paul Rudnick, who agreed to produce rewrites but only with the ominous proviso that his name appears nowhere on the credits. “To figure out the structure of that movie would require an undiscovered Rosetta Stone,” he later told The New York Times.

One scene that particularly irked him takes place in a lesbian bar, where the three women have gone to recruit Annie’s fiery teenage daughter Chris, played by Jennifer Dundas, to their avenging cause. Determined to prove how extremely comfortable they are in their surroundings, comedy ensues, as Elise storms the dance floor, and a photograph of Brenda’s ex-husband is mistaken for a woman. (“She’s butch” is the verdict of a woman at the bar.)

“I said, ‘OK, but why are they going there [to the gay bar]?’” Rudnick recalled. “He said, ‘They’re going to talk to Diane Keaton’s daughter, who is gay.’ I said, ‘She’s gay, but she doesn’t have a phone?’ He said, ‘Just write it.’ It was a very successful scene, and it makes no sense.”

Prioritizing comedy over narrative coherence may have paid off for Rudin, but in other areas, his influence has been alleged to have been more malign. In an investigation by The Hollywood Reporter earlier this year, former staffers accused Rudin of a career’s worth of bullying, harassment, and physical and emotional abuse. (An Apple computer monitor, a glass bowl, and a baked potato are among the objects with which he is alleged to have assaulted his juniors.) Rudin has since stepped back from producing to “work on personal issues I should have long ago”.

While no incidents in the article were specifically connected to the production of The First Wives Club, Rudin’s name on the credit sequence is a reminder of a Hollywood culture in which a clutch of powerful men terrorized and abused their subordinates. It rather clangs against the message of the film.

Rudin’s name is not the only MeToo-adjacent scandal associated with The First Wives Club. Last year, actress Heather Locklear, who played the small part of Cynthia’s ex-husband’s second wife, told Scrubs star Zach Braff’s podcast that she had asked (unsuccessfully) for her name to be taken off the credits because she had been made so uncomfortable by a “gross” scene in which James Naughton, who played her husband, circles her nipple on camera.

She initially implied that Naughton went beyond the direction he was given: “He actually outlines my areola with his finger. It didn’t say that in the script,” she said. Locklear later clarified on Instagram: “Oh no, I didn’t mean James Naughton did anything wrong. The script called for him to touch my breast.

“I was surprised that he circled my areola. We had not discussed the scene prior to filming. To be clear, I was never upset with James, just surprised.”

The original script direction, shared by a rep for Naughton, reads: “We see that Gil is subtly using his finger to feel Mary’s breast.” But viewed today, when intimacy co-ordinators are common, the idea that no one in the production felt the need to discuss a scripted moment of such intimacy and potential discomfort with either actor looks like a disturbing failure of safeguarding.

Allegations of sexism continued to dog the film into the 2000s. In 2006, in response to persistent rumors that a sequel was about to be commissioned, Hawn told The New York Post that she, Keaton, and Midler had turned down the project because of a perceived gender pay gap.

“I got a call from the head of the studio,” she recalled, “who said, ‘Let’s try to make it work. But I think we should all do it for the same amount of money.’ Now, if there were three men that came back to do a sequel, they would have paid them three times their salary – at least.”

According to Hawn, when the trio demanded higher salaries, Paramount declined to make the film. And while a television remake with a new cast arrived on American network BET+ in 2019 – to underwhelming reviews – the long-awaited sequel never materialized. (Hawn, Keaton, and Midler will, however, appear together for the first time on screen since The First Wives Club in a new feature, Family Jewels, in the next couple of years.)

Despite the shadow of sexism that hangs over the production, to a generation of women The First Wives Club will always be a feminist classic. In daring to write a popular novel that made middle-aged women the brains behind, not the butt of, the jokes, Goldsmith was a pioneer.

And we also have her to thank, indirectly, for putting one of the great comic actresses of her generation – Parker – on the map. In the film, Parker plays a style-obsessed New Yorker; it can hardly be a coincidence that less than a year later, Sex and the City creator Darren Star wrote the show’s pilot with Parker in mind for the role of Carrie Bradshaw. Not even Goldsmith’s tragic end could dim The First Wives Club’s legacy. As the song puts it: it doesn’t own her.