Consequence Of Sound

The First Wives Club and the Unsung Joys of Middle Age

BY NICO LANGON

SEPTEMBER 17, 2016, 11:00PM

Dusting ”˜Em Off is a rotating, free-form feature that revisits a classic album, film, or moment in pop-culture history. This week, Nico Lang revisits hit ’90s comedy The First Wives Club.

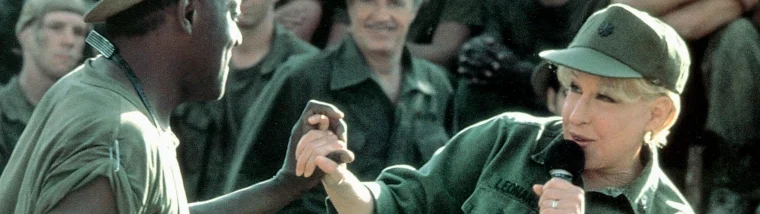

A movie can be important, even if it’s not very good. Such is the case with The First Wives Club, a frothy midlife crisis comedy currently celebrating its big 2-0. Starring Goldie Hawn, Diane Keaton, and Bette Midler, the film debuted in theaters in September 1996, sitting atop the box office for three weeks and topping out at a final gross of $105 million. Its success was sweet vindication following a troubled production. When the film’s original screenwriter, Robert Harling, bailed on the film to direct The Evening Star, a little-remembered sequel to Terms of Endearment, Paul Rudnick (In & Out) was tasked with finishing his script, which he claims “[made] no sense.”

For example, there’s a pivotal scene where Annie Paradis (Keaton) and her best friends from college (Midler and Hawn) visit a gay bar after Annie’s daughter comes out to her mother as a lesbian. Rudnick, who is openly gay, told the New York Times during a 1997 interview that he bristled at the logic of the scene. “OK, but why are they going there?’” Rudnick asked Scott Rudin, the ubiquitous producer behind such films as The Truman Show and No Country for Old Men. Rudin responded, “They’re going to talk to Diane Keaton’s daughter, who is gay.” Rudnick was still confused. “She’s gay, but she doesn’t have a phone?” he shot back. Rudin didn’t care if it adhered to common sense, just as long as it was funny. “Just write it,” he said.

That exchange is a perfect distillation of everything you need to know about The First Wives Club, which barely has enough plot to sustain a soap commercial, let alone a 90-minute film. It’s the kind of movie that must have made for a great pitch: Three women, approaching middle age and finding themselves traded in for younger models, decide to take revenge on their no-good exes. The resulting film, however, doesn’t appear to have been fleshed out much further beyond that concept.

If Rudnick suggested that one would need “an undiscovered Rosetta Stone” to “figure out the structure of that movie,” it would also require a dedicated construction crew and a whole lot of plaster.

Because the trio of women don’t have much else to do other than scheme, they spend a great deal of time knocking down walls, singing Lesley Gore songs, and laughing. In The First Wives Club, home improvement montages stand in for the more genre-typical Pygmalion-esque makeover scene. But even the mundanities of its plot raise unanswered questions: Why exactly do they need a private office to plot their revenge, especially when New York real estate doesn’t come cheap, when one of their spacious, luxury apartments will do? After all that time spent nurturing their lady cave, why don’t they seem to ever hang out there?

There’s a reason, though, that The First Wives Club, while imperfect, has maintained such longevity since its debut. In 2009, a San Diego theater company adapted it into a musical – which was successful, selling over 29,000 tickets despite poor reviews. That production was revamped in Chicago last year, and TV Land will be mounting a television version this fall.

What makes the girl-power comedy effective is not the clingwrap-thin story – which suggests 9 to 5 meets Spice World – but how it is told and who it is about.

The film marked a pivotal point in the careers of its trio of female stars, women who were aging out of a Hollywood system historically predicated on nubile youth and beauty. When the film debuted in theaters, its leads were 51, 51, and 50, well into a period of their lives when actresses experience rapidly diminishing returns. A 2014 study from Journal of Management Inquiry found that actresses’ paychecks peak when they are 34, while the value of their male counterparts continues to appreciate into their 50s. A male actor’s earning potential peaks when he’s 51.

The First Wives Club refreshingly dares to critique that double standard. Elise is a famous actress who has come to rely on plastic surgery to maintain her status as a leading lady. She laments the pressures women face to stay young, even though “Sean Connery’s 300 years old, and he’s still a stud.” “There are only three parts for women in Hollywood: babe, district attorney, and Driving Miss Daisy,” Elise tells her surgeon (Rob Reiner) when he refuses to give her another collagen injection. At this point, she’s already had plenty. “I want Tina Turner!” Elise yells. “Jagger! Fill ”˜em up!”

The film has the most fun with Elise, who is brashly vocal about her predicament. Playing on Hawn’s breezy charm, the actress is a career alcoholic who has been offered a key role in a film by a young, hotshot director. She believes she’s going out for the part of Monique, the ingenue. He wants her to play her mother instead. “Is this the face of a mother?” Elise drunkenly asks a bartender, gesturing to her lips. “Certainly not mine,” he says.

Each of these women, however, deals with the burdens of beauty culture in her own way. Annie (Keaton) is married to a husband (Stephen Collins) who dumps her for their couples counselor (Marcia Gay Harden). When he confesses that their marriage is over – after what appeared to be reconciliation sex – Annie asks why he tricked her into intercourse. A master gaslighter, he accuses her of manipulating him. Brenda (Midler) still has a torch burning for Marty (Dan Hedaya), a successful businessman who has left her for a younger woman obsessed with making her name in New York society (Sarah Jessica Parker).

What these women want is not revenge on the men who have cast them aside, but recognition for years of thankless work, the kind that wives and mothers put in every day. For instance, Brenda helped Marty get his start with a position in her father’s company, just to get ditched when he doesn’t need her to advance his career anymore.

These feelings of discontent are likely to be shared by the film’s target audience. In the workplace, women are structurally undervalued. Paid 77 cents for every dollar a man earns, female employees are often expected to do twice the work for half the pay, as well as a fraction of the recognition. Although Elise was the breadwinner in her marriage to an opportunistic Hollywood producer, he takes all the credit for her success during their divorce; of course, he still wants alimony anyway. An Upper East Side homemaker, Annie didn’t end up with the happy life she pictured, even as she pretends everything is perfect.

The First Wives Club is one of the few films made for a female audience in which its characters find fulfillment not by shacking up with a man, but by moving on from partners that don’t deserve them. Rudnick’s screenplay defines happiness not in monogamous rom-com terms, but as what we all want – to be respected and seen. During an era when precious few Hollywood movies even recognize the existence of middle-aged women, that message is still depressingly refreshing.