Winnipeg Free Press

Hershey runs risks in choice of film roles

Wednesday, January 4,1989

Forget the Oscars. If you really want status in Hollywood these days, you want to co-star with Barbara Hershey. You know she’ll give a great performance (and she’s such a respectful team player, she won’t overshadow you while doing it).

She’s a magnet for classy foreign awards (Hershey’s the only actress to win the Cannes Film Festival‘s trophy two years in a row). And moviegoers who have somehow managed to overlook Hershey’s versatility, passion and general screen radiance can’t fail to notice that she gets better-looking with each picture (it works for most guys, anyway).

But perhaps the biggest advantage to working with Barbara Hershey, for someone in the notoriously i n s e c u re

p r o f e s s i o n of moviemaking, is that some of her courage might rub off.

Takes risks

Few actresses consistently take the enormous risks that Hershey runs as a matter of course. Her daring goes beyond the serious thespian basics: Preference for variety over predictability, willingness to portray “unlikable” characters. She seeks out strong direct o rs w h o se v i s i o ns c o u ld overwhelm her, masticating costars whose egos could clobber her, projects agents call career-killers.

Not every time out, of course, but often, Hershey lays more on the line than comfortably necessary. Paragons of bravery

And the prestige and personal satisfaction have been growing accordingly, although she sees no need to mention it. True courage, like truly fine acting, doesn’t entail showboating.

It’s more than a serendipitous coincidence that in her four (four!) films of 1988, Hershey portrayed paragons of female strength and bravery. The domineering swamp matriarch of Shy People defended her clan against all outside threats. A World Apart‘s Diana Roth couldn’t have been a more different mother (though not necessarily a worse kind), an unflinching crusader for whom fighting South African apartheid was more important than family obligations. Mary

Magdalene in The Last Temptation of Christ was a woman so fierce in her love, she’d pay any price for it, including her temporal and immortal soul.

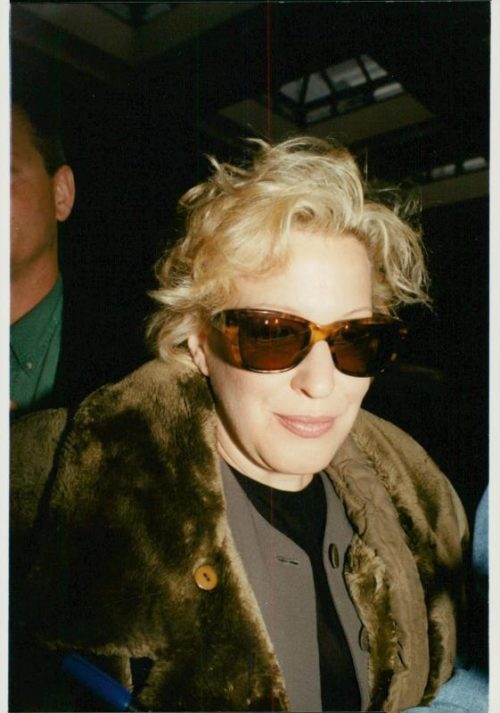

Finally, there’s Hillary Whitney Essex, who enjoys/suffers the ultimate act of courage that melodrama reserves for women: Dying nobly from a fatal disease. Beaches isn’t earth-shatteringly original; based on the book by Iris Rainer

Dart, it’s a female buddy comedy/weepie, co-produced by Bette Midler, f e a tur ing Bette Midler more-or-less playing Bette Midler, with Hershey around to provide a much-needed touch of class. She holds her ground against Hurricane

Bette, convincingly ages her repressed, WASPy character through the movie’s 30-year time span and dies just fine.

Number of challenges

“Beaches presented a lot of challenges,” Hershey, dressed in jeans and sweatshirt, says in the suburban L.A. home she shares with her 16-year-old son, Tom. “If I succeeded, you don’t notice them. I don’t like seeing the seams when

someone acts.”

Neither do we. So what are you doing in a movie with Midler? “I like working with different types of actors. The one thing I’ve constantly looked for, over the years, is variety, and by that I don’t just mean different kinds of roles and movies. I like working with different kinds of directors and actors.

“Bette is very volatile and interesting. You never know what she’s going to come up with. Sometimes she’ll stick to the script and sometimes you feel like you’re running after a moving train. Working with that kind of person feeds me and

brings out things which I feel I need. I like being her equal at that, even though I’m from a different world. I found our differences encouraging, complementary, amusing.”

Death scene

P e r s o n a l i t i es we re r a r e ly a source of problems on the Beaches set, according to Hershey. The sheer unwieldiness of the decades spanning plot was. “We shot way out of order,” Hershey recalls.

“One day we did my death scene, and the next day was my childbirth scene, which is high comedy.”

Mind-melting questions of tone and maturity level dogged every take. Hershey came away from the project disagreeing with the old showbiz maxim that comedy is harder than death.

“For me, the toughest part was the whole last section of the movie, the dying,” she says. “It meant a lot to me to do it right. When I do an accent, I want people from the place my character is from to be pleased with it. When I do a sickness I want doctors who look at it to be convinced.”

Hershey studied up on her debilitating movie malady, breath-blocking cardiomyopathy. She spoke with physicians and nurses who’d treated the incurable illness.

She did not interview victims because she considered that too vulture-like.