The Hollywood Reporter

Continental: SXSW Review

March 11, 2013

The director of “Small Town Gay Bar” hits the opposite end of the rainbow spectrum, cruising the storied New York bathhouse that gave Bette Midler and Barry Manilow their start.

Aptly described by the writer Edmund White as “a high point of hedonism,” the Continental Baths in New York City has acquired almost mythic status in gay social history as a temple of the sexual revolution. More celebratory than analytical, Malcolm Ingram’s documentary Continental is an engrossing if less-than-authoritative account of an establishment that could only have existed in the pre-AIDS bubble of the 1970s ”“ with primo lounge acts performing for a diverse cross-section of New Yorkers up front while gay men got it on in the liberating sexual playground out back.

Perhaps the most enduring testament to this intermingling of upscale entertainment with anonymous gay sex is the 1973 concert that yielded the now-rare recording “Eleanor Steber Live at the Continental Baths.” At that “black-towel event,” the renowned lyric soprano and musicians from the Metropolitan Opera performed a Mozart recital for an audience peppered with semi-nude guys on a cruising break. Those were the days.

The Continental was located in the basement of the Ansonia, a grand Upper West Side residential hotel built at the start of the 20th century. It represented an upgrade ”“ albeit with an infusion of Mob money and the occasional police raid ”“ from the seedy bathhouses that drew gay men in the pre-Stonewall era.

Clean and well-maintained, the complex in its heyday included a disco ”“ reportedly with the first Saturday Night Fever-style illuminated glass dancefloor and deejay booths ”“ 400 private rooms, lockers for guests to check clothing, a swimming pool, an orgy room, a boutique, a hair salon, and even a room for nondenominational religious services.

Ingram is too young a historical tourist to have experienced this bacchanal first-hand. His principal guide is Steve Ostrow, who owned and operated the Continental from 1968 until it closed in the mid-”˜70s, ushering an estimated six million pleasure seekers through its doors. A colorful character, Ostrow had a wife, two children and a mess of legal entanglements resulting from his independent finance company. When he spotted an entrepreneurial opportunity in the bathhouse business, he abandoned his pursuit of a career as an opera singer.

But one of the film’s chief weaknesses is that Ostrow is too eager to blow his own trumpet to be an entirely reliable witness, and Ingram doesn’t dig deep to substantiate his claims.

Via a petition with 250,000 signatures, Ostrow almost singlehandedly takes credit for the political shift that curbed legally sanctioned harassment of gays in New York. This sounds like a vast over-simplification. And at the peak of the Continental’s popularity as a crossover nightlife stop that allegedly counted Woody Allen, Diane Keaton, Mick Jagger, Salvador Dali and Johnny Carson among its guests, he recalls an unlikely sighting of Alfred Hitchcock emerging from the pool. Anecdotal evidence of Rudolf Nureyev’s regular late-night hunts for rough trade seems more plausible.

However, perhaps the difficulty of separating the factual from the apocryphal is an intrinsic part of any account of the Continental. What the film does do is evoke the atmosphere of the Baths and its position on the evolutionary map of gay cultural visibility. Ostrow and manager Jorge La Torre are the principal sources. But illuminating recollections about the wild promiscuity, the recreational drug use and the sexual egalitarianism also come from such pundits as White, Village Voice columnist Michael Musto, and Patrick Pacheco, editor of gay-skewing 1970s entertainment magazine After Dark, another great touchstone of its time.

Given the overlap with other documentaries, from Before Stonewall to Gay Sex in the 70s, not to mention books by writers like White and John Rechy, Ingram’s efforts to contextualize the birth of the Continental are fairly routine. The film becomes more compelling once it starts chronicling the introduction of live entertainment at the Baths.

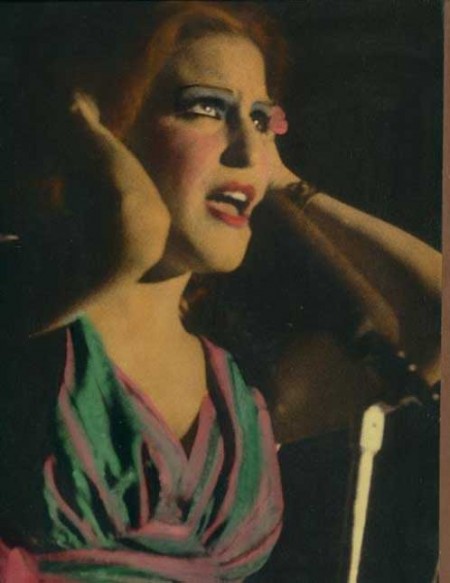

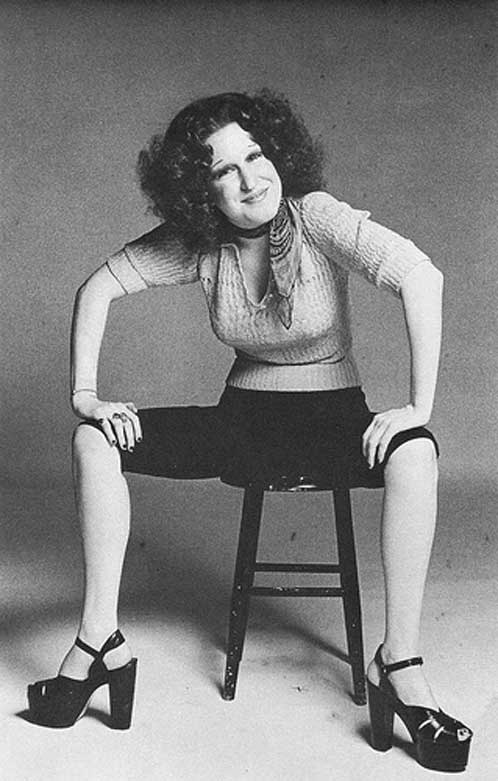

The insurmountable problem is the conspicuous absence of “Bathhouse Betty.” Performers from Sarah Vaughan and Cab Calloway to Labelle and Peter Allen graced the Continental’s tiny stage. But the entertainer most indelibly associated with the place was Bette Midler, accompanied by Barry Manilow on piano. Getting neither of them to talk leaves a hole at the center of Ingram’s film. With all due respect, Labelle founding member Sarah Dash and Warhol baby Holly Woodlawn are no substitute. There are some fun tidbits about Midler’s early career, however, including the claim that Ostrow dubbed her “The Divine Miss M” because he forgot the then-unknown’s name when introducing her to the crowd the first time.

Dance music aficionados will appreciate the input of Frankie Knuckles, the “Godfather of House Music,” who honed his skills as the Continental’s resident spinner. This strand that places the Baths among the progenitors of disco, paving the way for clubs like Studio 54 and Danceteria, might have benefited from further expansion.

Editor Sean Stanley shoots his wad with a punchy opening credits montage. But as the doc progresses, the shortage of exceptional archive material becomes apparent; a more diverse assembly of talking heads might have helped.

Where Continental also seems lacking is in the conflict. It’s inconceivable in that era that no Ansonia residents grumbled about lines of horny gay men around their block. But if they did, we don’t hear about it. A more detailed sense of how the establishment managed to integrate with the building and its management might have been opportune.

Ingram’s account of the end of the Continental is also superficial. Without much investigation, he identifies the primary factors as poor profit management and a core gay clientele that grew tired of being gawped at by straight sightseers. Perhaps its decline was driven as much as anything by the relentless turnover of what’s hot and what’s not that defines New York.

In the film’s closing moments Musto says that the Continental often seems almost like a Brigadoon dream, its unique juxtapositions being so far removed from any contemporary reality. In that sense, even if it’s not a fully satisfying chronicle, Ingram’s documentary serves a vital purpose for gay historians in bringing the legend to light.

Venue: South by Southwest Film Festival (Documentary Spotlight)

Production company: TCB Films

Director-producer: Malcolm Ingram

Executive producers: Nhaelan McMillan, Herb Campbell Jr., Salah Bachir

Directors of photography: Jonathon Cliff, Andrew MacDonald

Music: Neil McDonald, Paul Kehayas

Editor: Sean Stanley

Sales: Preferred Content/Submarine

No rating, 92 minutes.

Related articles